Are Us Old Folk More Spiritual?

Commentary by Walter Hesford

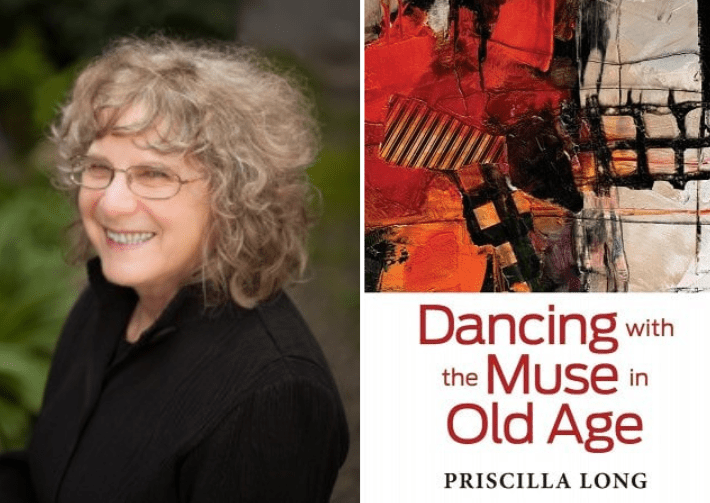

For Christmas, my 80 year-old-brother gave me, soon to turn 77, Priscilla Long’s “Dancing with the Muse in Old Age.” A celebration of artists and others who do great work in their later years, Long’s book includes a short discussion on “A Spiritual Life” in which she posits that “in old age many persons become more spiritual.”

Long cites Christina Puchalski, director of the George Washington Institute for Spirituality and Health. “As we age,” she asserts,” spirituality — broadly defined as a search for ultimate meaning and purpose and the experience of connection to the transcendent, to others, to nature and to the significant or sacred — plays a more dominant role in our lives than when we were younger.”

Examining myself, I’m not so sure about this assertion. Sure, since retirement, I have time to be more reflective, but don’t feel I’m searching for ultimate meaning. I don’t feel drawn to the transcendent.

I am drawn to the perspective on old age presented in Ecclesiastes by a person called in translation the Preacher or Teacher. His spectacular and depressing periodic sentence in this biblical book’s last chapter begins with an admonition: “Remember your creator in the days of your youth, before the days of trouble come, and the years draw near when you will say, ‘I have no pleasure in them’…” (12:1, NRSV).

The implication is that in old age we may be so beset by troubles that we no longer take joy in life and so forget to praise the creator of life. It is possible that those who experience severe pain will only be able to focus on that pain.

The course of life described in the sentence as it unfolds over six more verses is more entropic than transcendent. In vivid language the world of the old darkens, grinds down; “desire fails” (12:5). Finally “the dust returns to the earth as it was, and the breath returns to God who gave it” (12:7).

The last clause promises the transcendence of our breath, but lest we think our life that leads up to our end is thereby endowed with meaning, the Teacher next repeats his evaluation of our existence that he opened with: “Vanity [or vapor] of vanities, says the Teacher, all is Vanity”(1:2; 12:8).

Ecclesiastes does include some more encouraging words, including the famous, “For everything there is a season…” (3:1), but this oft-sung ode to life’s phases ends with the unsung, “What gain have the workers from their toil?” (3:9).

Is this gloomy or just realistic? Maybe there is something spiritual after all in the call to let go of illusions of worldly acquisitions, even worldly accomplishments.

Ecclesiastes is one of the great, disturbing wisdom books of the Bible.

The Book of Job offers more great disturbing wisdom that challenges conventional wisdom.

According to convention, Job, a community elder, has done everything right and so should be honored by his culture and his God. He has acquired great wealth and cared for his family and community. But, then, he loses everything, is thrown off center. He laments, rages, questions on an ash heap.

There is much that is disturbing in the story of Job. I just want to focus on the Lord’s response to Job’s questions and rage presented in Chapters 38-41. The Lord may be seen as bullying Job into submission, but I see the Lord as a wilderness guide, revealing to Job a wild world way beyond human control.

We and Job are treated to a trip through the cosmos. We see the deep sea, the constellations. Roaming the earth we see lions, mountain goats, wild ass, wild oxen, weird ostriches, mighty horses, soaring hawks and eagles doing their own thing (not to mention the incredible behemoth and leviathan).

Who isn’t belittled, rightfully decentered by a wilderness trip? Can old-age offer a similar belittling, decentering, enlightening experience?

Certainly it can physically. Many of us old folk experience physical limitations. I once rejoiced in shoveling heaps of snow; now I hope for flurries. Many of us need to reevaluate our status, our importance. A middle-aged stepson told me he has recently realized that he is no long the center of his sons’ lives — they have their own families, their own homes. As their grandparents, we are even more on the margins.

We old folks are also on the margins of the dominant culture. Movies, music, marketing are no longer aimed at us (though dubious drugs are). We are no longer prime consumers. Indeed, we often are trying to get rid of all the stuff we’ve accumulated.

Maybe this centrifugal activity puts us at one with the entropic universal. Maybe it helps us realize our dustiness, as do Ecclesiastes’ Teacher and Job (Job 42:6). Though earthy rather than transcendental, this realization may be spiritual.