Workplace complaints continue to grow against local Planned Parenthood

A track record of poor labor conditions, a deep dive into executive compensation, ghosted donors, an upcoming merger and a 20-year-old discrimination case.

News Story by Erin Sellers | RANGE Media

It’s been more than three months since we published our first story about union-busting and poor labor conditions at Planned Parenthood of Greater Washington and North Idaho (PPGWNI). PPGWNI leadership has been staying quiet and laying low: they’ve refused to comment publicly on their union-busting contract or allegations of poor workplace conditions.

In the last three months, RANGE has heard from more than a dozen current and former staffers who we didn’t originally talk to, but who saw their experiences reflected in the article and chose to reach out. We’ve heard from employees involved in the unionization efforts that interest in unionization has gone up, even among staff who had previously been skeptical about whether unionization was a good idea. We’ve also heard from donors who said that repeated calls to PPGWNI leadership seeking answers about union-busting and work conditions have gone unanswered.

Our ongoing reporting revealed a long history of toxic workplace allegations, including a discrimination lawsuit against CEO Karl Eastlund won by a former staffer in 2012; in-depth analysis of Eastlund’s large executive compensation package, frustration from some of PPGWNI’s biggest donors (one of whom just wrote the organization out of her will); and details about a recent merger between PPGWNI and the only other non-unionized Planned Parenthood affiliate in Washington, which could spell trouble for the fledgling unionization efforts.

So, without further ado, here’s nearly everything we’ve learned and verified since Dec. 19, 2024.

PPGWNI’s track record

After our first article came out, we received more than a dozen employee stories aligned with what we’d written, and what we realized is that Eastlund — and the Planned Parenthood affiliates under his leadership — has a questionable track record dating back to 2004.

In the early 2000s, there was another merger of regional Planned Parenthood affiliates, bringing together Planned Parenthood of Central Washington (PPCW) with clinics on the east side of the state and in Idaho to create what is now called PPGWNI. Because of the merger, and the new name for the affiliate, we missed a bit of Eastlund’s history with employee rights violations in our original reporting: a 2004 lawsuit from when he was the chief operating officer of PPCW.

According to reporting from the Tri-City Herald, Shannon Sharp of Benton County in Washington had been working for Planned Parenthood as a regional manager when she was diagnosed with degenerative arthritis in her neck. Rather than provide her the accommodations she asked for, Sharp said, PPCW fired her.

Planned Parenthood said it was for performance issues. Sharp’s lawyer Mike Saunders told The Herald that when Sharp was fired, she “had never received a negative performance review or reprimand, and the organization’s human resources department performed no independent investigation.”

In 2004, Sharp originally filed her lawsuit against both the organization and Eastlund, who was then the COO of Planned Parenthood of Central Washington, kicking off an eight-year legal battle.

For what happened to her and the subsequent eight-year trial, Planned Parenthood was ordered to pay Sharp $86,000 in back wages and $20,000 for emotional distress. Eastlund was separately ordered to pay her another $30,000 for emotional distress.

“After waiting more than eight years for her cause to be heard at trial, Ms. Sharp deeply appreciates the jury’s hard work and careful attention to the evidence in holding Planned Parenthood and (CEO) Karl Eastlund accountable for their discriminatory conduct,” her lawyer Saunders told The Herald.

By the time she received the jury verdict in her favor — in June of 2012 — her previous employer had merged with other clinics to become part of PPGWNI. Eastlund became CEO of the whole operation.

Neither Sharp nor Saunders could be reached for comment.

For their part, Planned Parenthood officials issued a statement in 2012:

“In our view, we followed all laws and professional protocols when we terminated her employment due to performance; however, recently a court agreed that the former employee’s claims had some merit. While we believe we followed all laws, we respect the court process, and we are grateful this legal process has concluded so that we can continue to focus on patient care.”

Though PPCW had evolved to PPGWNI, sources told us many of the issues persisted. We interviewed employees who had worked for the affiliate as far back as 2007, and they described many of the same problems: overworked and underpaid employees, a culture of silence and pressure to conform to Eastlund’s will.

Mark Cuilla, 2007 to 2013

In 2012, Mark Cuilla was a rising star at PPGWNI.

He had been volunteering at the organization in 2007 when he was offered a part-time organizer job. Less than a year later, in 2008, he was hired full-time.

Four years later, Cuilla received another promotion to Communications Manager for the entire organization, becoming the voice of PPGWNI, and working closely with CEO Eastlund to craft the organization’s statements and provide quotes to the media.

A few months into the job, one of Cuilla’s duties was to handle the press after Planned Parenthood and Karl Eastlund were found liable for employment discrimination in Sharp’s case. Just a few months later, Cuilla was fired while on medical leave.

It was a full circle moment that Cuilla described as “bizarre and surreal.”

“I was very sick,” Cuilla said. He gave his manager as much notice as possible, and then went to a treatment facility located outside of Spokane.

Under the Federal Medical Leave Act (FMLA) at the time, Cuilla was entitled to a total of 12 weeks of unpaid leave. At the end of the leave, Cuilla was supposed to be able to return to his job or an equivalent position, keep his benefits and “to be free of discrimination, retaliation or firing.”

Cuilla had planned to return to work at the end of December. On December 20, just 10 days before he planned to return, Cuilla’s medical facility alerted him that his treatment would need to stretch an additional month, to Jan. 25, 2013.

Cuilla sent RANGE a series of emails confirming that HR officials at PPGWNI had received and processed his request to extend his leave.

When Cuilla visited home for Christmas, though, he was shocked to find out that his supervisor from PPGWNI had called Cuilla’s then-partner and warned him that if Cuilla didn’t come back to work within the legally protected 12-week window of the FMLA, and instead came back on the Jan. 25 date that had discussed, he would be fired.

Even while he was at the treatment facility, on unpaid leave, with no access to his work phone or laptop, Cuilla was still completing work for PPGWNI.

“ I have several emails from when I was in treatment, on leave, having to do various things to manage the social media ads’ finances,” Cuilla said.

Despite asking him to do unpaid labor, there had been no similar direct communication about the leave extension being a problem, so hearing from his partner that his employment was now in danger was a holiday shock.

Current Spokane City Council Member Paul Dillon — who worked at PPGWNI as Vice President of Public Affairs and who we talked to in our original coverage — said that he had a similar experience: while he was on parental leave, he was asked to do work tasks by management at PPGWNI.

We emailed PPGWNI and called Eastlund to ask if the organization ever asks employees who are on any kind of unpaid leave, like FMLA, to complete work tasks while they are on that leave. We received no response, but will update this story if we do.

The next few weeks passed in a whirlwind. Before Cuilla returned to treatment, he sent an email on Dec. 28 telling PPGWNI leadership he would not be medically cleared to return to work in time for the deadline they’d given his partner.

He asked if the company would be willing to approve his unpaid leave past the legally required 12 weeks and terminate him instead on Jan. 28, just so Cuilla had time to get on his partner’s insurance and maintain the continuity of his healthcare.

Cuilla also sent a suggestion for a person who may be a good replacement to fill his role, and asked that his personal belongings left on his PPGWNI desk not be thrown away.

He also wrote, “I know it would typically be my job to write the talking points for [his departure from PPGWNI]. If I can have any say in how this is messaged internally (because I’m sure there will be people with questions), I just want people to know that I’m okay.”

Two weeks later, on Jan. 14, while back at the treatment facility, Cuilla received two emails. One notified him that if he wasn’t back to work by Jan. 15 (the next day), his “employment with PPGWNI would end,” but that they would still pay his insurance until the end of January. The other asked him to approve talking points that would be relayed to staff about his termination:

- “Mark’s leave has extended beyond the protections of the Federal Medical Leave Act. At this time, we must open the Communication’s Manager position to ensure the continuation of PPGWNI’s work.

- Mark has asked that we respect his decision to focus on his health.

- Mark has said he wishes the best for the staff and clients of PPGWNI; we, in turn, wish him well and thank him for the many contributions he made to our affiliate.”

“ I was devastated,” Cuilla told RANGE. “I had given so much to the organization and to feel like once I needed something, I was thrown away.”

Even after they fired him, even as he was still struggling to recover from his medical emergency, leadership at PPGWNI kept reaching out, asking him to do little tasks. He did them without complaint. “It’s embarrassing now,” to admit he kept helping, even after termination, Cuilla says, “but I was sick. I was young.”

Nearly a decade after his ordeal, in mid-December of 2024, Cuilla had finally decided that he was ready to move on from his heart-breaking experience at PPGWNI. He had deleted his entire old email account, where he’d forwarded correspondence from his managers at PPGWNI over a decade ago, trying to create a paper trail of his treatment at the hands of the organization. He’d taken a deep breath and moved on with his weekend, hoping to never think about PPGWNI again.

A few days later, a friend sent Cuilla the RANGE article on union-busting at PPGWNI, asking if he’d seen it. Cuilla told us it was an “oh shit!” moment. He hopped onto his computer to recover his old Gmail account, and then posted on Facebook, writing:

“This is not something I talk about publicly, but perhaps it’s time. It’s been over a decade since I was fired from PPGWNI while on medical leave. The way I was treated — the way I was used and thrown away — still affects me to this day, and I know I’m far from the only one with a similar story.”

Joy Peltier, 2012-2018

In 2012, Joy Peltier was just beginning her career at PPGWNI. Peltier began as a health educator and through a series of internal promotions, became the director of development, then vice president of development, then chief external affairs officer and finally, chief strategy officer (CSO).

Though Peltier was much closer to the top of the food chain than most of the current and former employees from PPGWNI that we’ve interviewed, it didn’t protect her from many of the same issues we’ve heard repeatedly from employees lower down the organizational chart.

Peltier spoke of being overworked, as she managed five different departments and a strategic initiative to stand up PPGWNI’s 501(c)(4) — which is a non-profit tax status designated for groups who are allowed to engage in political lobbying and advocacy, unlike their 501(c)(3) peers.

She said she had to fight for a pay raise to bring her up to a commensurate level with a male peer whose job tasks she was being asked to take on in addition to her own.

She also felt like she was responsible for protecting the employees in her departments from “the emotional chaos [CEO Karl Eastlund] exuded.”

Once, Peltier said, Eastlund told her part of her job was “to make sure that the staff don’t organize.” It made her uncomfortable, but at that time, Eastlund’s strategy was less aggressive: she was told to just make PPGWNI such a great place to work, that staff didn’t want to unionize.

“ I felt weird about that, but then thought if people feel good and happy and our employment engagement scores are good and it feels genuine, then I’m okay with it,” Peltier said.

PPGWNI and Eastlund did not respond to a request for comment on whether Eastlund had ever told Peltier, or any other members of management, to keep staff from organizing.

For most of her time at PPGWNI, Peltier said she had a good relationship with Eastlund.

“ I think he does have the heart for the mission and he is trying to do right by the organization and the patients,” she said. “He rescued PPGWNI out of financial turmoil when he became the CEO. PPGWNI could have ended up getting absorbed by Seattle if he didn’t turn it around financially. I don’t want to paint him like he’s a 100% evil villain.”

But when Eastlund got stressed, she said, he changed.

“ His interpersonal skills and his ability to lead in a healthy way can be challenging for him,” Peltier said. “He gets overly emotional and can make rash decisions about staffing if he’s feeling the stress.”

Soon after her promotion to chief strategy officer, the good relationship with Eastlund shifted. At the time, Eastlund was telling her that she was his “succession plan,” that she’d be hired as CEO when he retired, but he also became more demanding and less supportive.

“As soon as he gave me that raise, he started treating me pretty badly,” Peltier told RANGE, saying it felt as though, “because I made such a high salary, I wouldn’t leave and he could abuse me as much as he wanted to.”

Peltier said she knew what was coming next. She had seen it before. “Every person that had my job before me, I watched him fire and push out,” she said, “So as soon as his attitude toward me changed, I knew I was next. I knew it. And so I made other plans.”

As she described her choice to leave PPGWNI, Peltier got choked up.

“I felt like Planned Parenthood was the job I was born to do. It broke my heart when this all happened and I felt like I had to leave for my own mental health,” she said. “When I talk about Planned Parenthood, I still say ‘we.’ I just feel like my heart is still there. I still donate. Well, I haven’t been doing as much lately because of the situation.”

Unlike all of the other past employees we’ve interviewed, Peltier got some level of closure for her treatment by Eastlund:

“ A few years after I left, he actually invited me out to coffee and apologized to me for treating me the way he did,” she said. “So I know that he knows that the way he treated me was not great and that he regrets that I left. At least, that’s what he said.”

Eastlund and PPGWNI did not respond to a request for comment.

Marty Briseño, 2018-2022

In 2021, Marty Briseño appeared in an 83-second video advertisement for the advocacy arm of the national Planned Parenthood organization.

Briseño seems proud — proud of being transgender, of his Mexican immigrant identity, and proud too of his employer — Planned Parenthood of Greater Washington and North Idaho — and how supportive they had been of all aspects of him.

“I am the person who one day arrived at a place where the mountains meet the sky and finally found a home in Planned Parenthood,” Briseño says in the Spanish voiceover played over shots of him smiling in front of the PPGWNI office in Spokane. “A home where I am not just accepted, but I am welcomed for who I always was. A place where my life begins again.”

Briseño was featured in PPGWNI’s annual report that year, too, his smiling face next to a QR code linking to the video, and above a section about PPGWNI’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion efforts that begins “Care. No matter what.”

Within two years, Briseño would be gone from PPGWNI, working instead at the billing department of a Spokane cosmetic surgeon.

Briseño’s story aligned closely with what we’ve consistently heard from other employees: he felt overworked at PPGWNI and undercompensated for labor he described as stressful. He’d started in the call center, which Briseño described as short-staffed. He hustled there until he started to feel burnt out.

He applied for an internal promotion and didn’t get it, but was offered a transfer to the billing department, a lateral move that came with additional duties but no pay raise. Briseño said he frequently had to work extra hours off the clock to ensure he didn’t fall behind.

“It was too much for one person,” he said.

On top of that, Briseño was beginning to medically transition, and PPGWNI’s medical benefits functioned like golden handcuffs — his work insurance covered his gender-affirming care.

As one of the transgender employees on staff, he was asked to lead internal diversity training, which he did happily and for free, hoping to advance his career and move into a higher position doing Diversity, Equity and Inclusion work for PPGWNI. That advancement never came, though he later advocated for himself in a meeting with a manager and started receiving a small stipend each time he presented.

In the fall of 2022, Briseño requested to be transferred out of billing back to the call center, thinking it would be less responsibility for the same pay. His manager told him that instead, it would be best if Briseño and PPGWNI parted ways.

He remembers asking “are you firing me?” and being told, “No, we think we should separate at the end of the year.”

“I think they were trying to get me to quit, so they didn’t have to pay unemployment,” Briseño said. He started applying for other jobs.

When he left near the end of 2022, he was “barely making $18 an hour,” Briseño said. “I was there for five years and I was barely making $18 an hour.” At the time, Washington’s minimum wage was set at $14.49.

His new job at the cosmetic surgeon’s office isn’t as personally meaningful, Briseño said, but he’s making about $10 an hour more than he did at PPGWNI.

Between 2018, when Briseño started at PPGWNI, and 2022, when he left, Eastlund’s compensation had jumped from $234,515 to $399,979.

Eastlund’s executive compensation

While his employees were fighting for raises and being asked to do unpaid work, Eastlund’s salary was growing greatly. As we’ve previously reported, Eastlund makes a lot of money, and the current number may be even higher. The salary numbers we have come from PPGWNI’s most recent nonprofit tax filing — known as a 990 — for the tax year 2023.

Historically, PPGWNI has filed its tax returns closer to the middle of the year — they filed those 2023 tax returns in June of 2024 — so we should know in a few months if his salary has grown again.

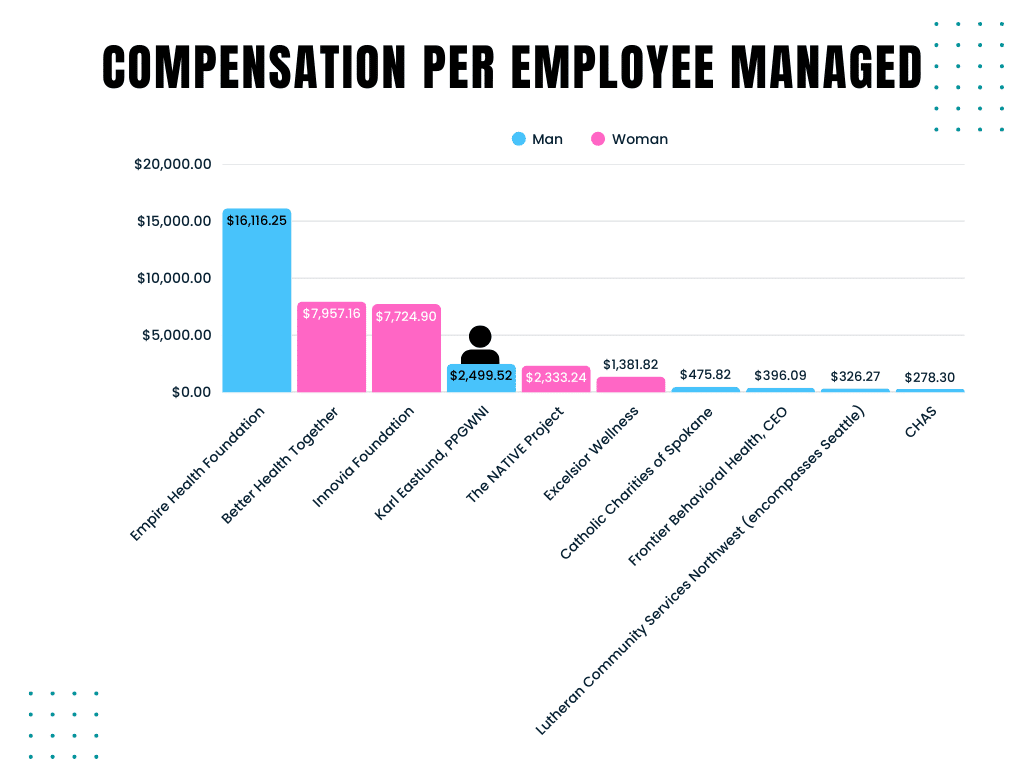

To get a sense of whether Eastlund’s compensation was in line with other similar leaders, we compared his compensation with executive compensation data for comparable local nonprofit healthcare organizations and foundations, as well as Planned Parenthood affiliates across the U.S. that have similar levels of yearly revenue to PPGWNI.

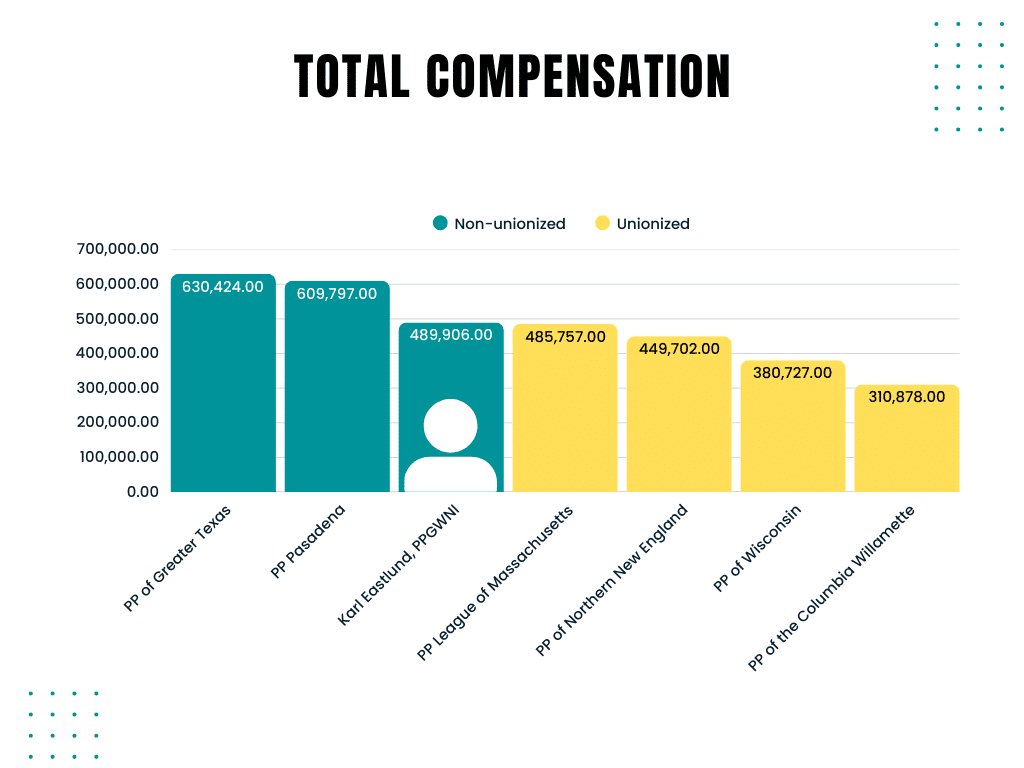

- CEOs of non-unionized Planned Parenthood affiliates — like PPGWNI — generally make more than CEOs of their unionized peers. Eastlund’s compensation follows that trend; his total compensation is higher than the CEOs of all other unionized affiliates with comparable annual yearly revenue.

- Perhaps more surprising for an organization dedicated to reproductive health, Planned Parenthood may have a gendered pay gap issue: with one exception, male Planned Parenthood CEOs we looked at made more than their female counterparts. Only Sheri Bonner of Planned Parenthood Pasadena and San Gabriel Valley makes more than her male peers.

- When local cost of living is factored in, the exception for Bonner goes away. She lives in a much more expensive area of the country and when that cost of living is accounted for against CEO compensation, she makes less than Eastlund and Ken Lambrecht, the CEO of Planned Parenthood of Greater Texas.

- When you adjust the CEOs’ compensation by cost-of-living, Eastlund makes more than every other CEO of comparable affiliates, except one: Lambrecht. Lambrecht successfully shut down employee unionization efforts at his affiliate in 2021. Additionally, Lambrecht’s pay is so high it’s been specifically noted in a 2023 report from anti-abortion advocacy group American Life League’s STOPP International, weaponizing the discrepancy in pay between Planned Parenthood’s male and female CEOs as part of their campaign against reproductive rights.

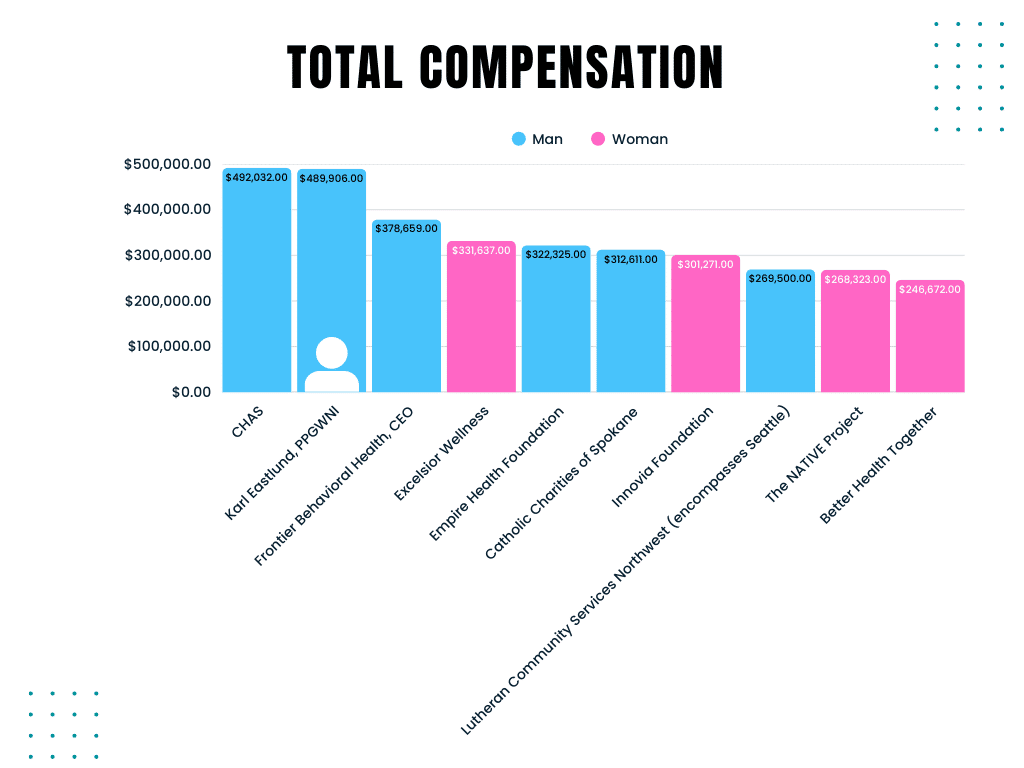

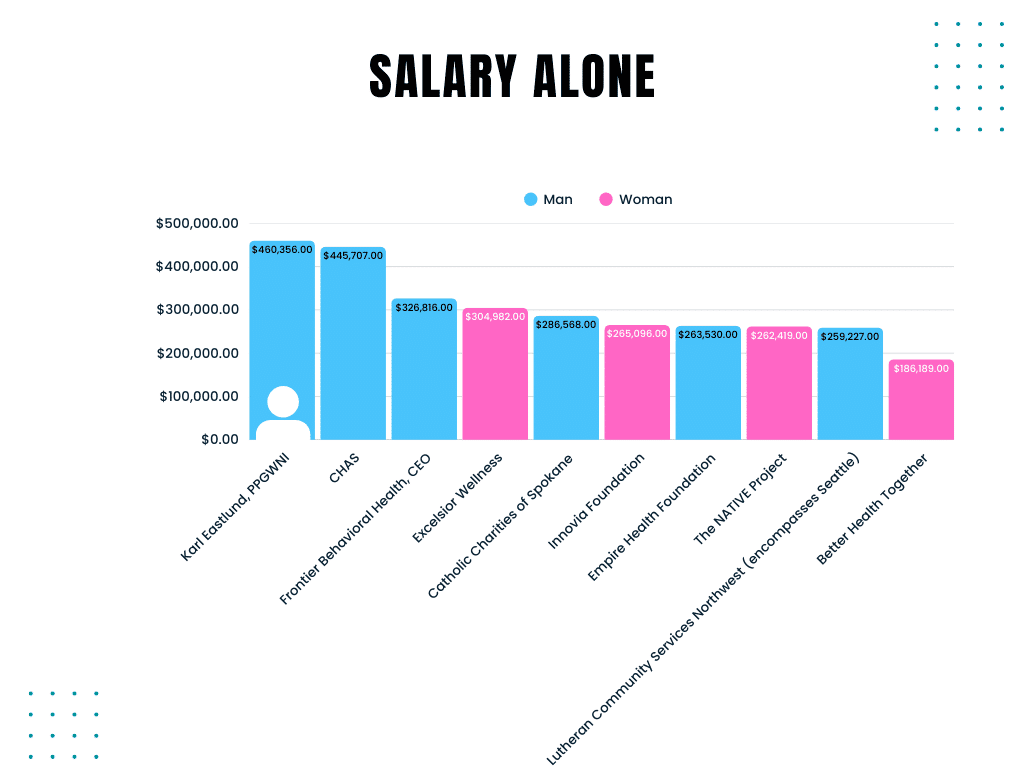

- Compared to CEOs of local Spokane nonprofit healthcare organizations and foundations with similar sizes and/or industries, Eastlund is also near the top of the pack. He made about $2,000 less than Aaron Wilson, the CEO of CHAS — who managed 1,572 more employees than Eastlund.

- Eastlund also made $100,000 more than the next highest paid CEO: Jeff Thomas, CEO of Frontier Behavioral Health in 2023 (Thomas has since passed), who managed 760 more employees than Eastlund.

- If you consider salary alone, and not additional compensation, which can include bonuses and benefits, Eastlund makes more than every other local CEO of a comparable nonprofit organization.

Flip through a slideshow of graphs 👇

Editor’s Note: The slides comparing Eastlund’s executive compensation against the compensation of other executives at local health foundations and nonprofits incorrectly state that Excelsior’s CEO was a woman, as of 2023. The CEO was (and is) Andrew Hill. However, the top paid employee at Excelsior Wellness in 2023 was Tara Willow James, the Chief Medical Officer, whose salary is reflected in the graphs.

Dodging donors

RANGE isn’t the only one who can’t get a call back from Eastlund. Some of PPGWNI’s biggest donors told us they have been ghosted too, after reading our initial report and calling both Eastlund and representatives of PPGWNI’s board looking for answers.

Right after our first story broke, Sharon Smith, of the Smith-Barbieri Progressive Fund, began to make calls. To Eastlund, to the board president, to board members, to former employees. She wanted answers.

In 2015, the foundation gave $500,000 during the capital campaign for the building — the largest grant the foundation has ever given to this day, which accounted for 25% of the total $2 million raised during the capital campaign for the building. The gift was so large, PPGWNI honored it by putting the Smith-Barbieri name on the side of the new building.

When the Pullman campus of PPGWNI was fire-bombed that same year, the fund donated another $40,000 as part of a matching campaign to leverage a total of $250,000 for the organization.

Disclosure: Smith-Barbieri Progressive Fund has also given grants to RANGE, and serves as our fiscal sponsor. Per our policy on community journalism, developed in conjunction with our Advisory Board, we hired an editor from outside of the RANGE team to edit the story for both content and potential bias. More on our commitment to journalistic independence at the end of the story.

Despite her foundation’s long history of generosity and her permanent, public affiliation with PPGWNI as the sponsor of their Spokane campus, leadership of the organization didn’t pick up Smith’s calls. Board President Alberto Saldaña did answer one call, Smith told us, but quickly got off the phone after finding out the nature of her inquiry and has not returned subsequent calls and emails.

“I’d love to talk to anybody who wants to talk to us, because this is really insane what’s happening,” Smith told RANGE. “We’re very uncomfortable with being affiliated with an organization that does not provide appropriate workplace rights and protections. It’s unacceptable to us.”

Smith said one of the big reasons Smith-Barbieri donated the money for the building was because they wanted to help provide a facility that the patients deserved, and ensure that even low-income patients had access to high quality medical care and facilities.

“It makes us so sad to think I’ve got these patients telling me that they had great care at Planned Parenthood and now, knowing what’s happening behind the scenes,” Smith said, “… knowing that those employees, who gave [patients] that care and great service, are not being treated well and fairly and equitably and appropriately — it’s devastating. And, for the foundation, it’s horrifying and disturbing.”

As of Wednesday, March 26, more than three months after initially reaching out, Smith said she still hasn’t heard from anyone at PPGWNI.

Karn Nielsen, another longtime donor, who sat on PPGWNI’s board from 2014 to 2020 and served as board president for three of those years, also spoke to RANGE about her recent frustrations with leadership.

“I firmly support the mission of Planned Parenthood,” Nielsen said. “Every time I went to a board meeting I just felt really good about what we were doing in the community.”

Prior to our story, Nielsen had already been hearing rumblings about employee frustration and mistreatment, but as soon as she read about union-busting at PPGWNI, she was spurred into action. She immediately emailed the board and any employees she still knew, canceling her monthly donation and voicing her disgust with the union-busting contract. She “heard absolutely nothing back.” Nielsen told RANGE she knows four or five major donors who have been similarly stonewalled, but declined to give names because that information was shared with her in confidence.

“The idea that [staff are] trying to unionize and [Eastlund’s] trying to break that just is not acceptable,” Nielsen said. “I’m appalled at what they’re doing and trying to silence all this.”

Nielsen had sent PPGWNI $150 every month for the last 10 years. Once, she threw in an extra $5,000 to support a specific fundraiser. Like Smith, Nielsen was also a major donor for the new building in Spokane, contributing $300,000.

Her dedication was so deep, Nielsen said she even set aside a piece of her estate to give to PPGWNI in her will. After PPGWNI chose not to respond to her emails, she wrote them out.

Eastlund and PPGWNI did not respond to requests for comment. We reached Saldaña by phone, but as soon as we identified ourselves as RANGE Media inquiring about PPGWNI, Saldaña responded, “Hello? Hello?” We called him back, in case it was a connection issue, but he didn’t pick up. Subsequent phone calls and a message were not returned.

The Merger

Since our initial report, PPGWNI leadership has mostly stayed quiet — with the exception of emailing our first story out to their whole staff (thank you!).

Last week, though, they made a big announcement: PPGWNI is absorbing the only other non-unionized Planned Parenthood affiliate in Washington — Planned Parenthood Mount Baker. The merger brings PPGWNI’s total number of clinics to 14 — their current 11 and three clinics formerly managed by Planned Parenthood Mount Baker that will shift to PPGWNI.

According to reporting from KREM2, PPGWNI CEO Karl Eastlund will stay at the helm of PPGWNI. The CEO of the Mount Baker affiliate will be retiring.

Marketing materials for the merger say the move will help ensure the future of the three clinics managed by the Mount Baker affiliate on the west side of the state.

It also adds a significant chunk of new employees to the PPGWNI workforce. The most recent data we have for each organization are tax records covering 2023, but back then PPGWNI had a total of 196 employees and Mount Baker had 59. Assuming those numbers are still somewhat accurate, absorbing the Mount Baker staff will increase PPGWNI staff by about 30%.

Because unionization requires the support of over 50% of employees who vote in the union election, by adding a large chunk of new, nonunionized employees who haven’t been privy to union conversations or witnessed the working conditions, the merger has potentially made unionization efforts harder.

When we spoke to employees for our first story, they told us it was already difficult to organize within PPGWNI because the 11 clinics are spread across Central and Eastern Washington. This new batch of employees will be located in the northwest corner of the state, even farther from the rest of the PPGWNI clinics and the unionizing efforts.

Staff downsizing often follows a merger. Part of the goal of many mergers is to streamline costs, which often means eliminating positions.

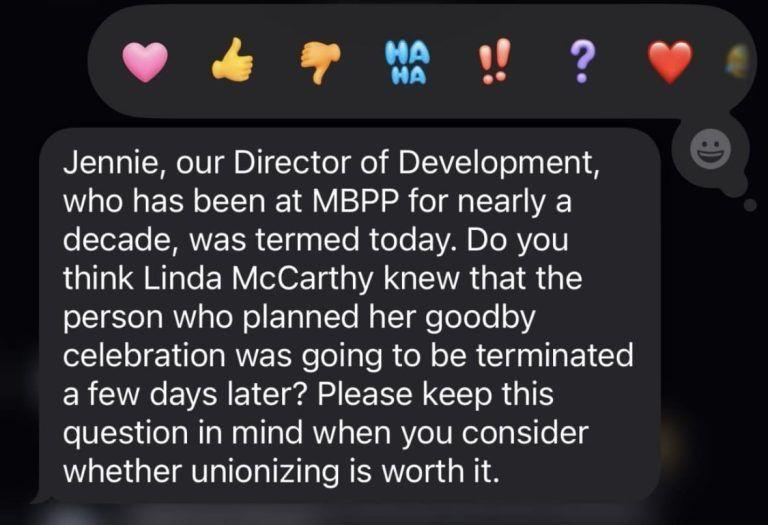

The organization hasn’t wasted any time on that front. One day after the merger was announced publicly, two employees came in to work to find their positions had been eliminated.

An email sent by PPGWNI leadership to the full staff of the newly merged entity stated that the employees would receive “a generous severance package, job search support and reference to help with their next steps.” According to an employee at PPGWNI who asked to use the pseudonym “Chris” to protect their employment, the “generous severance package,” came tied to nondisclosure agreements.

The layoffs were shocking for staff, Chris said, because both employees had been with Planned Parenthood affiliates for years. The Mount Baker employee whose position was terminated had even organized the retirement party for Linda McCarthy, the CEO of Mount Baker who left just before the merger, handing the reins of the new entity to Eastlund.

The abrupt layoffs seemed even more cruel because there were open positions within PPGWNI at other clinics that the employees who had been let go had experience for, Chris said.

It’s created even more of a culture of fear. Because the letter sent out by PPGWNI also stated that if “more staffing changes are needed, they will happen later this spring or early summer,” employees are now on edge, fearful they may lose their job with no notice, especially if leadership thinks they may be involved in unionization efforts.

“Hannah,” a former employee of the Mount Baker affiliate, who also asked to use a pseudonym out of fear of retaliation in the tight-knit healthcare community around Bellingham, told RANGE that, when she read our first piece on PPGWNI, she recognized a lot of similarities to the work environment she had experienced at Mount Baker. She described high turnover rates for health center staff, favoritism from upper leadership and low pay: in her years at Mount Baker, she didn’t receive a single raise, she said, not even a cost-of-living-adjustment.

While she thought there could be some positives to the merger, like greater resources and a better business strategy, Hannah is worried for her former colleagues under Eastlund’s leadership.

“[We need] to make sure that we’re holding the organization accountable, especially in a time of change where we can’t just assume that things are only changing for the better,” Hannah said.

Hannah also said the addition of the Mount Baker staff to PPGWNI might not be a death blow to unionization efforts after all, telling RANGE conversations about unionization at Mount Baker had already begun before the merger was announced.

UFCW 3000, the union working with PPGWNI staff, declined to comment for this story.

Additional reporting contributed by Luke Baumgarten.

If you are an employee of PPGWNI or Planned Parenthood Mount Baker who was laid off after the merger was announced, you can get in touch with RANGE reporter at 509-850-0488 or erin@rangemedia.co.

RANGE Editor’s Note: Sharon Smith is co-founder of the Smith-Barbieri Progressive Fund, which has provided funding for RANGE. RANGE maintains rigorous control over our editorial content and, while we may call funders for comment on stories where their perspective is relevant, they have zero oversight or input into anything we write. Per our policy on community journalism, developed in conjunction with our Advisory Board, we hired an editor from outside of the RANGE team to edit the story for both content and potential bias.