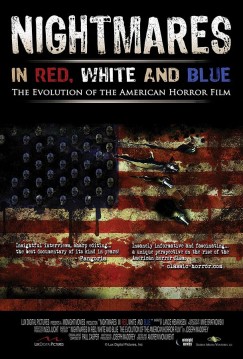

Who are the people we need to watch out for? Since public shootings have become commonplace, this question may be on many Americans’ minds. In Andrew Monument’s 2009 documentary “Nightmares in Red, White, and Blue” (currently streaming on Netflix), about the history of the American horror film, filmmaker Mick Garris (“Bag of Bones,” “Critters 2”) addresses the matter directly:

If you meet all the people who make horror films, you discover they are very non-violent, they’re politically active and knowledgeable and anti-war. They have opened themselves up to all of these possibilities, and it’s the people [who have] repressed them who are the ones you have to look out for.

I have spent a lifetime almost never raising my voice to anyone. I was taught from birth to abhor violence, and I see cruelty to animals as one of the world’s greatest evils. As a survivor of bullying, I know that emotional and physical violence is extremely destructive. So why do I cozy up to films that feature bloodthirsty vampires, crazed killers, or sharp-toothed aliens? And what is all of this horror doing to me?

Horror films address primal human fears in ways that are emotionally disturbing, not just intellectual. We feel when we watch these movies; they’re not easy to dismiss or forget. We experience a level of empathy for the protagonists that a non-horror film might fail to cultivate. Good horror films aren’t always very violent, but when they are, the violence is wrenching, upsetting, and significant.

Yet even your cut-rate slasher film has something to offer, albeit less intentionally. We humans are terrified by death; most of us either face it grudgingly or struggle to deny the reality of it. If our mortality petrifies us, the fragility of our bodies isn’t far down the list of primal terrors. Most slasher films do clumsily what the subgenre of “body horror” does very much on purpose, and sometimes with great flourish and insight. We humans can fall apart, degrade, or otherwise cease to be in a sickening variety of ways. Body horror reminds us, in offputting detail, of the simultaneous preoccupation and revulsion we feel about that.

Human beings have always incorporated violence into their art, likely because violent urges exist somewhere in each of us. Violence had survival value to most humans at some point in our species’ history. If, individually and as a society, we can acknowledge and deal with the scarier parts of ourselves, rather than simply repressing them, we stand a better chance of stemming the current tide of violence.

It’s healthier to see violence as terrible and irrevocable rather than cartoonish and easily dismissed. If we can have a conversation about it instead of pretending that only “monsters” have violent impulses, all the better. These approaches may help us begin to understand acts of violence that can seem, on the surface, incomprehensible.