He’s a committed atheist; his wife comes from a line of Southern Baptist preachers. Yet 23 years and three kids later, they are still happily married.

What’s their secret? McGowan, 51, has just written “In Faith and In Doubt: How Religious Believers and Nonbelievers Can Create Strong Marriages and Loving Families,” to help other couples considering what he calls a “religious/nonreligious mixed marriage” succeed.

“The key is to talk about your values,” McGowan said from his home in Atlanta. “A lot of time we mix up the words ‘values’ and ‘beliefs.’ Beliefs are what you think is true about the universe. Is there a God? Where do we go when we die? But values are what you believe are important and good. When you get couples talking about values they find out they share a tremendous amount, even if they don’t share beliefs.”

That’s what McGowan and his wife, Becca, did. While she believed in one God, she did not believe salvation could be had only through belief in Jesus. And he agreed that he could go to church with her — and did, for many years, with their children.

“This isn’t about the way I see the world — it’s about whether I can be in a loving, enduring relationship with someone who sees it differently,” McGowan writes in the book. “And when the question is framed in that way, the ‘big’ theological questions are actually smaller and less important than the social values questions. On those, this atheist and his Evangelical wife had a solid match.”

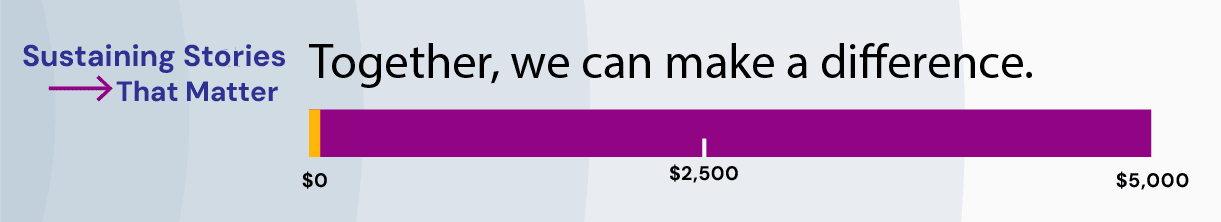

In their book “American Grace: How Religion Divides and United Us,” social scientists Robert D. Putnam of Harvard and David E. Campbell of the University of Notre Dame show that in 1950, about 20 percent of all U.S. marriages were interfaith. Today, that number is 45 percent.

Nearly one in six (59 percent) of the religiously unaffiliated say they have spouses who are religious. Susan Katz Miller, author of “Being Both: Embracing Two Religions in One Interfaith Family,”said her work among couples of different faiths shows there is a need for more information for couples where only one partner is religious.

“I think religious/nonreligious couples face the same issues as interfaith couples — namely, respecting each other and supporting each other without having to agree on a set of beliefs or practices,” she said. “We need to hear more stories from these families and the variations we will hear in the stories of humanist/Muslim, atheist/Christian, agnostic/pagan couples, etc., will be an important part of this new narrative.”

McGowan, too, saw a need for a book on religious/nonreligious unions in his work with parents raising children outside a faith tradition. He is the author of two books on parenting without belief and writes a blog on the same subject.

“It was an absolute drumbeat throughout the parenting work I was doing,” he said. “People would ask me for a resource and there wasn’t any. It became overwhelming at a certain point, and I knew this book had to be written.”

Yet there was precious little data on marriages between religious and nonreligious couples when McGowan sat down to write. So he commissioned a study with demographer Mary Ellen Sikes at American Secular Census to paint a portrait of such unions.

The sample was small — just under 1,000 respondents from around the world — but the results are intriguing:

- Two-thirds of religious/nonreligious couples were aware of their difference before they married, but 29 percent did not know of the difference until after the union.

- About half of all respondents expressed negative emotions about the difference, while 34 percent said they were “indifferent.”

- In cases where the couple were unaware of the difference before marriage, 22 percent said it was because one partner experienced a religious conversion — or deconversion — after the marriage.

In those cases, the difference can sometimes be insurmountable, or nearly so. McGowan writes of one couple, Hope and David, parents of five who were both born, raised and married as conservative Baptists. David had been headed for ministry when he lost his faith entirely.

After much unhappiness, unsuccessful counseling and lots of discussion, the pair decided to stick it out. “I wish I could say it was easy to make up my mind to love David and then move forward with that decision, but it was not,” Hope says in the book. “I realized that we weren’t likely to end our marriage in a peaceful or friendly way, in part because of David’s traumatic childhood, so I decided to stay. Five years later, I’m really glad I did.”

McGowan’s own wife, Becca, experienced a change of faith in their marriage — she now considers herself a secular humanist, a migration she says her husband had little to do with. And while McGowan said he laments the loss of a second worldview for his children’s upbringing, he remains optimistic about the benefits of marriage between people who do and don’t believe in a god.

“We have these black and white views of each other, the religious and nonreligious,” he said. “But the common ground is extraordinary between the two, and the fact that this is overlooked is something I really wanted to look at. You don’t have to go searching as far or hard for the common ground.”