In 2010, the US apologized to Native Americans. A new spiritual movement aims to recognize it

By Emily McFarlan Miller | Religion News Service

Negiel Bigpond’s family was forced from their land and marched across the country on the Trail of Tears.

Bigpond, who is Yuchi, was sent away from his family as a child to what were known as Indian boarding schools, where he remembers being made to cut his hair and dress differently, as well as being punished for speaking his Yuchi language.

Now he’d like an apology — or, rather, he’d like the United States to acknowledge the official apology it already has made to Native American peoples, which was buried in a defense spending bill and signed into law in 2010.

And he’s not the only one.

Bigpond and Sam Brownback, the former Kansas governor, senator and U.S. ambassador, have launched a movement to raise awareness of the apology and ask President Joe Biden to formally recognize it in a ceremony at the White House Rose Garden.

“I just felt like it was time that the Native people receive an apology from this nation,” Bigpond said.

“I believe it would help — not so much that we would get granted great finances and buy the land back or give the land back or anything like that. It was a spiritual thing.”

Brownback and Bigpond met more than five years before the apology passed, when Brownback invited a group of Native American leaders to his Senate office. A friend whom Brownback described as a “person of faith” had told the senator that it was time for the country to be reconciled to Native Americans after years of wars, broken treaties, forced removal of Native nations from their lands, boarding schools that separated Native children from their cultures and other mistreatment.

“It captured my heart,” Brownback said, and he wanted to talk with both community leaders and spiritual leaders about what that might look like.

Two hours into what was meant to be a half-hour meeting with a number of Native American leaders, he said, “I asked them, ‘Well, what should we do?’ and that’s when Negiel said, ‘Well, I think there needs to be an official apology.’ That’s what really launched it.”

In 2009, Brownback sponsored a joint resolution in the Senate to acknowledge and apologize for the United States’ long history of mistreating Native Americans.

Language from that resolution was later added as an amendment to the 2010 Department of Defense Appropriations Act.

In it, Congress “recognizes that there have been years of official depredations, ill-conceived policies, and the breaking of covenants by the Federal Government regarding Indian tribes.”

It also “apologizes on behalf of the people of the United States to all Native Peoples for the many instances of violence, maltreatment, and neglect inflicted on Native Peoples by citizens of the United States.” And it encouraged the president — then President Barack Obama — to acknowledge the wrongs of the U.S. against Native nations “in order to bring healing to this land.”

But, in the years since, no president has ever presented that apology to tribal leaders or read its words aloud publicly. Few people are aware it was made.

And, Bigpond and Brownback wrote in a recent op-ed for The Washington Post about the apology, “To many Native people, an apology not expressed is worse than no apology at all, just another set of meaningless words buried in official treaties and broken promises.”

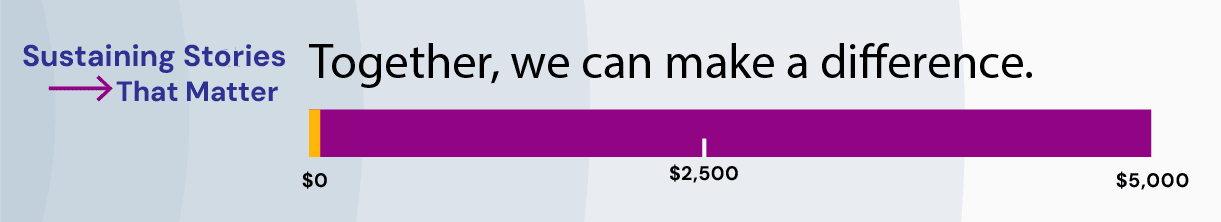

The two have launched a movement simply called “The Apology” that includes a website and video series with information about the legislation, as well as a social media campaign calling on the White House to formally acknowledge it.

It comes as the horrors of residential and boarding schools for Indigenous children in Canada and the United States are being revisited. In the past few months, hundreds of Indigenous children’s buried remains were confirmed near the grounds of Canadian residential schools, and the Department of the Interior announced a Federal Indian Boarding Schools Initiative to look into the treatment of children in the U.S. Several children’s remains were also identified at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania and returned to their families for reburial.

“We’re in a season of reconciliation,” said Brownback, who served as U.S. ambassador-at-large for international religious freedom in the Trump administration.

“This is a time where we’re wrestling with these sins of the nation — whether it was towards the First Nations, whether it was slavery — where we’re wrestling with these problems now and their consequences. It’s time to deal with it,” he said.

Efforts have been made in the past to draw attention to the apology.

In 2016, Bigpond — a Christian who founded and leads Morning Star Church of All Nations in Oklahoma — organized an event called All Nations D.C., in which Native American Christians from 27 tribes across the country gathered at the Washington Monument to offer a prayer of forgiveness to the nation.

“We’ve already planted the seed of forgiveness even though we’ve never been asked,” Bigpond said.

In 2012, Mark Charles, a Navajo writer and speaker who ran as an independent for president in 2020, gathered about 150 Native Americans from across the country to read the legislation aloud in English, Navajo and Ojibwe in front of the U.S. Capitol. Charles had only just become aware of the apology himself and wanted to make it widely known.

He also wanted to draw attention to the ways he feels it is inadequate: It mentions no specific tribe, treaty or injustice and ends with a disclaimer, he said.

Charles urged Native Americans not to accept the apology, “not out of anger, not out of bitterness, but out of respect — out of respect for ourselves, out of respect for our ancestors, the boarding school survivors, the people who were massacred and even out of respect for white America,” he said.

“We deserve a better policy, and they can give a much better policy than what was signed into law on Dec. 19, 2009,” Charles said.

Bigpond and Brownback call the apology a “spiritual” issue.

They hope it will be a first step that can lead to ongoing conversations about what reconciliation looks like. Brownback pointed to the example of Georgetown University, which asked for forgiveness for selling enslaved people in the past and raised money to benefit their descendants, though he was careful to note the apology includes language clarifying that it neither supports nor opposes reparations.

And, Bigpond said, “An apology would be good medicine to heal people and heal the land.”