What questions do you have about Judaism? Submit them online, or fill out the form below.

How are children raised up in your faith tradition?

My parents emphasized the importance of reading and formal education since I was very young. That I would attend college and get a bachelor’s degree was more or less a given. My parents also passed on to me a strong love of the arts. This isn’t surprising, as numerous art forms — music, literature, theater, and film — have great historic importance in the Jewish tradition.

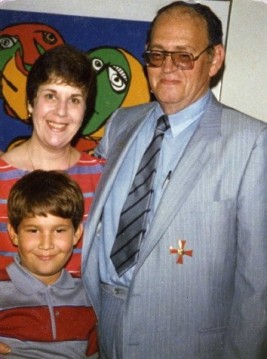

My formal Jewish education happened mostly outside the home, but of course my parents oversaw it. I attended Sunday school from a young age and eventually prepared for my bar mitzvah. My family went to synagogue regularly — if not every week, then certainly often. I was raised in a Reconstructionist congregation in which the overwhelming political and theological flavors were progressive. My father in particular raised me not to be uncritical or unquestioning when it comes to Israel. He maintained what I consider a healthy skepticism about the actions of the Israeli government. Based on my interactions with peers, I imagine that many American Jews of my era were raised with a more unequivocally pro-Israel stance.

Holidays are a big part of many Jewish children’s experience of their culture and faith tradition. Chanukah is a minor religious occasion, but it now serves as a Christmas-like opportunity for gift giving and receiving as well as the consumption of tasty fried delights. Passover can be boring and/or fun for a child depending on the length and nature of the Seder. Many Jewish families have a Seder at home, which helps to make Judaism something personal and relevant rather than simply a tradition to study in Hebrew school.

I would imagine that many Jewish households emphasize God’s greatness and the importance of fulfilling at least some of the mitzvot. In other homes, perhaps tikkun olam (healing the world) is the primary Jewish value that parents discuss, since it is broad and positive enough to encompass a lot: community service, choosing a helping profession, giving tzedakah (charity), and so on. Some parents may instead, or additionally, stress the words of Rabbi Hillel: “That which is hateful to you, do not do to your neighbor. That is the whole Torah; the rest is commentary.”

In my household, God was not a frequent subject of conversation. Being a good person, and a well-rounded, open-minded, educated one, certainly was. My parents also emphasized the importance of following one’s passion rather than simply doing work that is practical but joyless. I can see this as an integral part of tikkun olam, since people tend to do more to heal the world when they’re actually interested in their work.

Do some Jewish parents expect their children to marry Jewish? Of course. My parents voiced no such expectation, for several reasons, and I ended up intermarrying. I would guess that the children of parents who discourage intermarriage are less likely to do so. However, the rate of intermarriage in America has been rising steadily, and I don’t know how strongly Jewish parents are urging in-marriage these days. Again, it probably depends on family denomination and parents’ personal experiences and beliefs about intermarriage and Judaism in general.

My maternal grandparents were Holocaust survivors, and my mother is a Holocaust Studies professor. I learned about the Holocaust relatively early in my life, both from my mother and from some children’s books about the Holocaust. I’m not sure how young Jewish children tend to be when they learn about the Holocaust from their parents, but I would think that few American Jews reach adolescence without having some version of that conversation. Those whose grandparents are survivors may learn more, and learn it sooner, than those who don’t have as direct a family connection to the Holocaust.