A friend is a loved one who awakens your life in order to free the wild possibilities within you.

— John O’Donohue

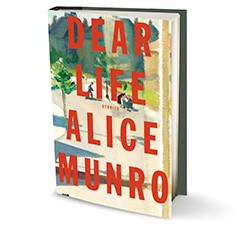

It was summertime. And during the nighttime, the young Alice was haunted by the persistent and unwelcome idea that she might deliberately hurt her sister, that she might strangle her as she slept in the bunk below.

Munro was so distressed by this idea — was it a nightmare or a vision? — that she would get out of bed and, in the warm darkness of the summer, walk around the outside of her family’s house. This went on for a number of days, perhaps even for a number of weeks — Munro walking in order to run away from her dreams — when she realized that her father was quietly waiting for her on the stoop of their home. In spite of her fearful sense that she ought not to confess her reason for being awake and outside, that such a confession would change things between the two of them forever, Munro told her father what it was that weighed so heavily upon her.

This is what Munro writes next:

My father had heard it. He had heard that I thought myself capable of, for no reason, strangling little Catherine in her sleep.

He said, “Well.”

Then he said not to worry. He said, “People have those kind of thoughts sometimes.”

And Munro says that from then on she could sleep.

I suppose that story caught my attention because it reminded me of the several times in my own life when another person has shared a bit of brief and simple wisdom with me and, in a real sense, that wisdom has set me free. In high school, for instance, I was wondering about becoming a professional actor. A veteran of the stage listened to my aspirations and said, “Don’t do it if you don’t have to.” Hearing his advice, I understood pretty much right away that, while I did “have to” be part of a creative enterprise — nurturing beauty was and is a big part of my calling — I did not “have to” act. And so I became a stage manager and, later on, a priest.

More recently, I was working with an individual whose hurt and whose anger sometimes showed up in startling and even destructive ways. Watching the dynamic, my boss Bill Ellis observed, “It’s way harder to be that person than it is to work with that person.” Through Bill’s words, I was able to understand what was going on in a whole new way. Now, that didn’t always make my interactions with this hurting individual easy. But it did markedly increase my ability to approach those interactions — and other interactions like it — with patience and with empathy.

I could give more examples. And I bet you could as well. Here are the elders, the friends, the teachers, even the people whom we have met only through books. The folks who, whether or not they intended to be wise, managed to say something that opened a door, that named the truth. Here are the people whom we encounter when we are wandering around in the insomniac darkness of our anxiety. The people who share simple and beautiful words. Words which allow us to go back home and go to sleep.