Guest Column by Ann Ciasullo

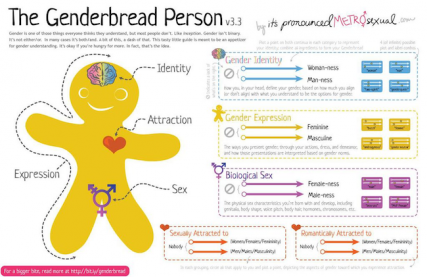

As a professor of Women’s and Gender Studies and a feminist scholar, I have long been interested in issues of gender, sexuality, and identity. In graduate school at the University of Kentucky, I wrote my dissertation on cultural representations of lesbianism and the lesbian body in the twentieth-century United States. As a postdoctoral teaching fellow at the University of Oregon, I developed courses on gender and popular culture and sex, gender, and the body. It was in this latter course that I asked students to consider the relationship or interplay between biology (sex) and culture (gender), or what we more commonly call the “nature/nurture” debate. In teaching the course, I shared concepts that I already knew well—for example, that sex and gender are two very different things—and ones that I had just come to grasp. Among the latter was the notion of gender identity or expression—the sense of oneself as a gendered being, the sense that the declaration “I am a man” or “I am a woman” aligns with how a person feels about him/herself. And I learned the importance of separating gender identity or expression from sexual orientation: that is, how one feels one’s gender is distinct from to whom one is attracted. Put another way, my studies and my teaching have helped me to see the many strands that constitute one’s gendered and sexual self.

My learning continues to this day, especially in the past year, when the issue of transgender access to bathrooms came to the forefront. I must confess that despite my understanding of trans issues and despite my teaching about them, I have found the questions that have sprung up in the wake of the bathroom issue to challenge me in ways I could not foresee. For example: last year, Mount Holyoke College, an all-female college in Massachusetts, decided to suspend its yearly production of Eve Ensler’s The Vagina Monologues because, they argued, the play “offers an extremely narrow perspective on what it means to be a woman. . .Gender is a wide and varied experience, one that cannot simply be reduced to biological or anatomical distinctions.” Knowing that millions of women worldwide are still subject to abuse, rape, and murder because they are women, because they have vaginas, I found the college’s decision to be perplexing at best and blind and reductive at worst. Put another way, this year has surfaced a whole range of questions about what constitutes a woman or a man, and despite all my knowledge and learning, those questions have made my second-wave feminist head spin.

By calling myself a “second-wave feminist,” I mean that I was trained by the feminist teachers/scholars/activists who, in the 1970s, agitated for greater rights and recognitions for women in the United States. These are the women who changed laws and policies; who examined aspects of traditional womanhood such as heterosexuality and motherhood and reframed them as institutions, or structures with rules, regulations, and mandatory obligations; and who, perhaps most significantly for today’s topic, demanded that we separate sex from gender, arguing that the conflation of the two had resulted in centuries-long oppression of women. In her groundbreaking 1975 essay “The Traffic in Women,” Gayle Rubin uses the phrase “sex/gender system” in order to describe “a set of arrangements by which the biological raw material of human sex and procreation is shaped by human, social intervention.” Rubin identified gender as “the socially imposed division of the sexes.” Put another way, Rubin and other scholars gave us the idea that while sex (male/female) is fixed, gender (masculinity/femininity) is mutable; gender is, in the most widely used phrase, “socially constructed,” which means it can be disputed, socially reconstructed, built anew. The sex/gender distinction made way for all sorts of challenges to gender-based social inequalities, from the elimination of sex-segregated ads in the New York Times in the late 1960s to the Education Amendments of 1972, including Title IX, which, among other things, opened up the world of competitive sports to women and gave us a generation of remarkable athletes and coaches such Abby Wambach, Serena Williams, and Pat Summitt.

And here’s where things sometimes get tricky for second-wave feminists in relation to trans issues. If, as second-wave feminists have long held, femininity is socially constructed; if “maleness” and “femaleness” are the result of cultural forces, or “nurture”; and if the many accoutrements of femininity—makeup and dresses and high heels—are imposed upon women by patriarchal forces, then how do we explain the fact that many trans women embrace these constructs as a way to express their “essential self”? For example, in the now-famous Vanity Fair article on Caitlyn Jenner, author Buzz Bisinger notes that as Bruce, Jenner would “secretly wear panty hose and a bra underneath his suit so he could at least feel some sensation of his true gender identity.” Put another way, trans narratives of coming to terms with an inner sense of “manhood” or “womanhood” suggest that there is something essential about gender, that for trans people nature trumps nurture. So what’s a feminist like myself, one who has long towed the “cultural construction” line, to do?

The thing to do, I believe, is twofold. The first is to listen as a way to learn. In her piece on the trans bathroom legislation, Julia Stronks simply and beautifully observes, “The stories of others changed me.” As a professor of English, I know the power of stories. Through stories, we are invited into worlds radically different from our own and asked to feel what the other feels. We travel down the Mississippi with Huck and Jim; we watch the extravagant parties alongside Jay Gatsby; we experience the racial hatred thrust upon the Invisible Man. Without stories, there would be no imagination, no diversity, and perhaps most importantly, no empathy. So I thank those who are brave enough to tell their stories, people with celebrity status like Laverne Cox and people in our own community, like Luke. These stories may challenge our long-held beliefs, and that is a good thing: growth comes from such challenges.

The second thing, and perhaps equally important from a feminist perspective, is to understand that our cultural derogation of trans people—especially the fear that trans people will pose a threat to the safety of women and children—actually stems from a familiar place: sexism and misogyny. For as much as I’m not a fan of Caitlyn Jenner (not because she’s trans, but because she’s politically regressive), the jokes and memes that circulate about her ridicule her because she “gave up” being a man to be a woman. This choice is seen as humorous, laughable, incredible, really. A mock-up of a Wheaties box features Caitlyn with text next to her declaring that the cereal “contains no nuts.” Another features her face not on a box of Wheaties but on a box of Froot Loops. What makes her “fruity”? Her deviation from gender norms—specifically, the norms of masculinity. For this she is relentlessly derided. Conversely, trans men are often understood as being “frustrated” with their inferiority as a woman and therefore “opting out” for a more privileged position in society. Rejecting their manhood, trans women are seen as infidels; identifying as men, trans men are seen as interlopers. When thinking about trans issues, then, the sex/gender distinction can still be helpful, because the immense hatred that trans people face—verbal abuse, psychological suffering, and physical violence and death—stems from the belief that your biological sex and gender expression had better align with one another, or else. What fuels the discrimination and violence committed against trans people is patriarchy and male privilege, which depends upon sexual and gender binaries and the discipline of bodies in order to sustain itself.

Theorizing is useful, important work; Rubin’s work of identifying and analyzing the sex/gender system led to significant social change. But the battle cry of the second wave feminists is useful to recall here: the personal is political. With regard to trans issues, honoring the personal—how trans people understand their sense of self, and how they want to be recognized by others—is the start of something potentially transformative for our gendered selves.

Dr. Ann Ciasullo read these notes at the last Coffee Talk, July 2. View a video of the entire Coffee Talk here.

Thank you again for creating a open, honest forum for conversation at Coffee Talk. I hope you will be asked back soon!