It has been most of three weeks since I returned from Bend, Ore. and the seminar presented by Marcus Borg and Dom Crossan on “Reading the Bible as a Christian.” My reaction to the three days remains very positive, even upon critical reflection, for though I didn’t hear much that was truly new to me, I got a lot out of the way Crossan in particular framed the issues, and the supporting evidence he developed for his basic arguments. One of his arguments continues to nag at me, and it nags at me more because of what the implications are if it is true, rather than because of the possibility that he is wrong. Indeed, if he is wrong the tension created by this particular argument dissolves, and I get to sleep better at night.

Crossan argues that Jesus engaged in a form of non-violent resistance to Roman Imperial rule in Palestine. He cites several examples of such resistance during the first century of the Common Era, at least two of which Jesus would have known about, though he wouldn’t likely have participated in them. This resistance was centered in presenting to the people of Palestine an alternative way of understanding real kingdom, and it featured Jesus pitting the notion that God is to be found in the armies of Imperial Rome and the Divine Caesar against his notion that God is to be found in the poor and the marginalized. Not a war horse, but a donkey, not an emperor but a peasant, is the figure and type of God’s presence in the world. I am not certain that this kind of protest would have been enough to get Jesus killed, but depending on how far he went it might have been, particularly if it got enough people actively questioning what we might somewhat anachronistically call the theological underpinnings of Roman Imperial rule. Certainly there is evidence from the first three centuries of the Common Era that Christianity was from time to time considered some sort of threat to Rome because it was subjected to periodic, highly sporadic, mostly localized, persecutions.

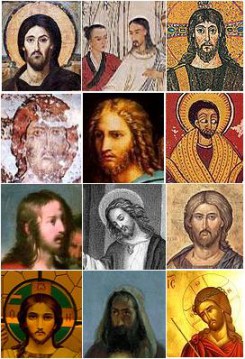

My nagging thought is that if Jesus himself was engaged in a protest that was potent enough to get him killed, it is hard for me to avoid the conclusion that in killing him the Romans succeeded altogether. For without the physical presence of Jesus, Christianity began to adapt itself as much as it could to Empire, even going so far as to abandon the pacifism that had been one of its hallmarks for the first three or four generations after the crucifixion. By the time Christianity became legal in the fourth century under Constantine the Great, and then the only legal religion a few decades later under Theodosius, it is pretty clear that the Empire had changed Christianity more than Christianity had changed the Empire. What had started, in Crossan’s terms, as a non-violent protest movement dedicated to overturning the standard notion of what constitutes true power succumbed to the lure of temporal might, and began to persecute others with an even greater vigor than it had experienced. Jesus had been knocked off his donkey only to be seated on a charger. The peasant king now looked as much like Caesar as Caesar ever had. I suppose we could say that in the end Rome lost, for the empire ultimately faded away, while the worship of Jesus as Lord continues unabated to this day. But if Jesus was a non-violent protester, then Rome won, at least in spirit, for by the start of the 13th Century Pope Innocent III commanded the largest army in Europe. Was ever a victory more complete? Was ever a transformation more total?

That bothers me; it bothers me a lot. For if Crossan’s argument is true, then the clear implication is that spiritual history spent a long time moving in the wrong direction. Not just the message, but the life of Jesus, the Gospel that was Jesus, got subverted by the people who loved him most and wanted to follow him best. I have no doubt that this wasn’t deliberate, but if that is what happened, then the words Jesus spoke from the cross: “Father forgive them, for they know not what they do” he must have continued to say for centuries afterward, even to this day. There is much for me to do before this nagging gets resolved, but one thing seems clear. The study of the early history of Christianity is absolutely vital for understanding how best to be Christian today. This is not just an academic exercise any more, a matter of interest to specialists. If we wish to be faithful to Christ then we owe it to ourselves to make a real effort to find out what Jesus was about, and to live faithfully with the results of what we discover.

From my course on the historical Jesus, I understood the most common view to be that Jesus was apocalyptic, meaning he believed the coming of the “son of man” to be immanent. He wasn’t interested in politics because the end was near.

Also, Jesus was crucified because he disrupted the Passover (overthrowing the tables). There was some evidence that Pilate had put to death another similar figure who had disrupted the Passover just a year or two before Jesus. The Romans had two basic priorities with the provinces they ruled: keep the peace and keep the taxes coming.

There are lots of views about the perspective Jesus brought to his ministry. I was for a long time persuaded by Albert Schweitzer’s belief that Jesus was an apocalyptic preacher who turned out to be wrong. For the past several years now I have been less and less sure about that. As I mentioned, I am not so sure about Crossan’s view of things either. The immediate cause of his arrest and crucifixion could well have been the “incident” in the Temple, and it certainly is plausible. There is something both comforting and disturbing about the possibility that it was that simple, that arbitrary.