There’s been a lot of talk about millennials and their place in the ever-changing religious landscape in America. Millennials my age have been through a lot in since the turn of the century that has shaped our spiritual paths in ways rarely experienced by previous generations of Americans. We were in grade school and middle school when we watched the events of Sept. 11, the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq on our TVs. If we weren’t exposed to the Muslim-American experience before these events, we became bystanders to Islamophobia, misunderstanding, fear and the tension between our American identities and our religious experiences. Over the course of a few years, we were seeing things through an interfaith lens whether we wanted to or not.

Taking these experiences with us to college, we find ourselves constantly in flux, experiencing many new things, learning new concepts and meeting new people. In many ways this happens to every generation. As Joseph Campbell outlines, we are all on the hero’s journey and need to remake ourselves in life. Whereas we are no different in this respect from earlier generations, I daresay there has never been another generation who has had to deal with these complex issues in such a short amount of time. We came to age thinking the world was a very large place only to be told by businessmen that through globalization it is now smaller than ever. We grew up being told to love our neighbor form the pulpit, only then to witness them being suspected of terrorism because they were Muslim. We grew up learning that God is love, only then to see His LGBTQ children (c)overtly left alone on Sundays. Why are millennials different than earlier generations? Because we had to come of age wrestling with these concepts and then make sense of our world.

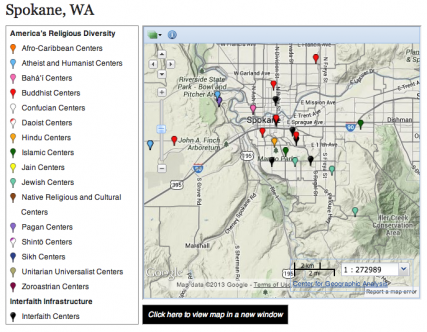

The old sentiment many people still hold of millennials being lazy, egotistical self-centered entitled kids, who spend more time tweeting one another than meeting face-to-face shows a misunderstanding of who the millennials are, and an almost willful ignorance to get to know them. As a millennial myself, Rachel Held Evans’s thoughts were right on when she wrote candidly about “Why Millennials Are Leaving the Church“. I’ve heard many church leaders bemoan this article, but I think she's on to something here. And the data is striking on this subject. The Pluralism Project at Harvard University just launched the new interactive web resource “On Common Ground”, where they look directly at the city of Spokane’s diverse religious landscape. The site features an interactive GIS map infused with U.S census data with local religious data to showcase an unprecedented view of the city’s faith makeup. After only a few minutes, it is clear to anyone using the site that the data support Held Evan's claims. If we are to resurrect the church, how can we engage the next generation?

Perhaps the answer lies in how our spiritual paths are defined. This came up time and time again at the Georgetown University’s Berkeley Center for Religion Peace and World Affair’s Millennial Values Symposium, and something I wrote about there. Millennials are great at acting on things in which we believe. We have a shared commitment to compassion and faith, but we choose to act upon these values differently. I mean, we practically ended Joseph Kony’s efforts to kidnap children in Uganda by pressuring the U.S government in an online campaign to act. And that was done in our free time. Imagine if we were engaged to help promote clean energy. Immigration. Homelessness.

We are no different than earlier generations in this respect. Where we differ is that earlier Americans have not had to deal with the aftermath of war, religious illiteracy, politicization of the religious and the distrust of our neighbor in such a short amount of time. We recognize that this needs to change, and we are ready to work. We have chosen to fight injustice with the tools of our time. We want to be the change.

What we don’t want is to be overtly pandered to by our leaders for our wallets, our votes or our souls. Growing up with the Internet also means we’ve grown up with advertising firms and focus groups. We understand how the game works. Half of us are marketing majors already. So instead of being treated as a means of commodification, millennials want to be involved in the conversation and part of the solution. How will we work together to change the church? As Held Evans points out, ask us. You may be surprised at what we think.

Join us at 10 a.m., Sept. 7 for our next Coffee Talk where we'll discuss “Engaging Millennials.” Oberst is a panelist.

Skyler,

I definitely agree that Millennials don’t want to be patronized, manipulated, and used as some kind of platform by politics, advertising, and the like.

And I would also add one thing to the description of the conditions under which Millennials grew up: rapidly evolving technology, and especially the way in which people interact, get news, and learn about the world. The internet means there is no time delay on news. I’ve seen a Facebook comment break news long before it hits the local paper, and even comment feeds that have a jump on the news reporters covering a live story (granted, the comment feed wasn’t exactly fact checking, but there were some grains of truth amongst other wild speculation). The means by which we get and share news, and the ubiquity of devices on which we can do this, has both positive (Kony) and negative (an entire generation accused of interacting on Twitter more than having face-to-face interactions) affects. Millennials do want to make a difference — but their activism may look somewhat different than previous generations’ activism.

I look forward to the Coffee Talk on Sept. 7!