Did you watch the terrific History channel three-part documentary about Ulysses S. Grant that aired last month?

Grant is such a complex and all-but-forgotten figure whose reputation has been improving as the southern narrative about the civil war has been discredited by contemporary historians. It was not a war for states’ rights. It was a war fought to abolish the abomination that was human slavery.

I was struck by something Grant wrote in his autobiography, explaining why his surrender terms to Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia were relatively generous. Loosely quoting, Grant said he could feel empathy for his vanquished foes because they fought so valiantly and died for a cause they believed in even though that cause was wrong.

That comment resonates today as we grapple with the divisive issues tearing at our country. All of us tend to view those opposed to our deeply held personal opinions as wrong, and in these times, even evil. That black and white construct makes civil dialogue all but impossible.

Can we accept the notion that people who see the world differently can be sincere – but also wrong? And on what basis can we determine rightness and wrongness? Is such a calculation possible?

I recently retired from the University of Idaho where, among other things, I have been teaching media ethics for 10 years. The course was built around development of a personal ethical decision-making process based on reconciliation of conflicting personal and professional values. At the heart of any ethical dilemma are clashing values that must be reconciled before the problem can be resolved.

That same process of resolving clashing values is at the heart of community problem solving and is fundamental to a civil society.

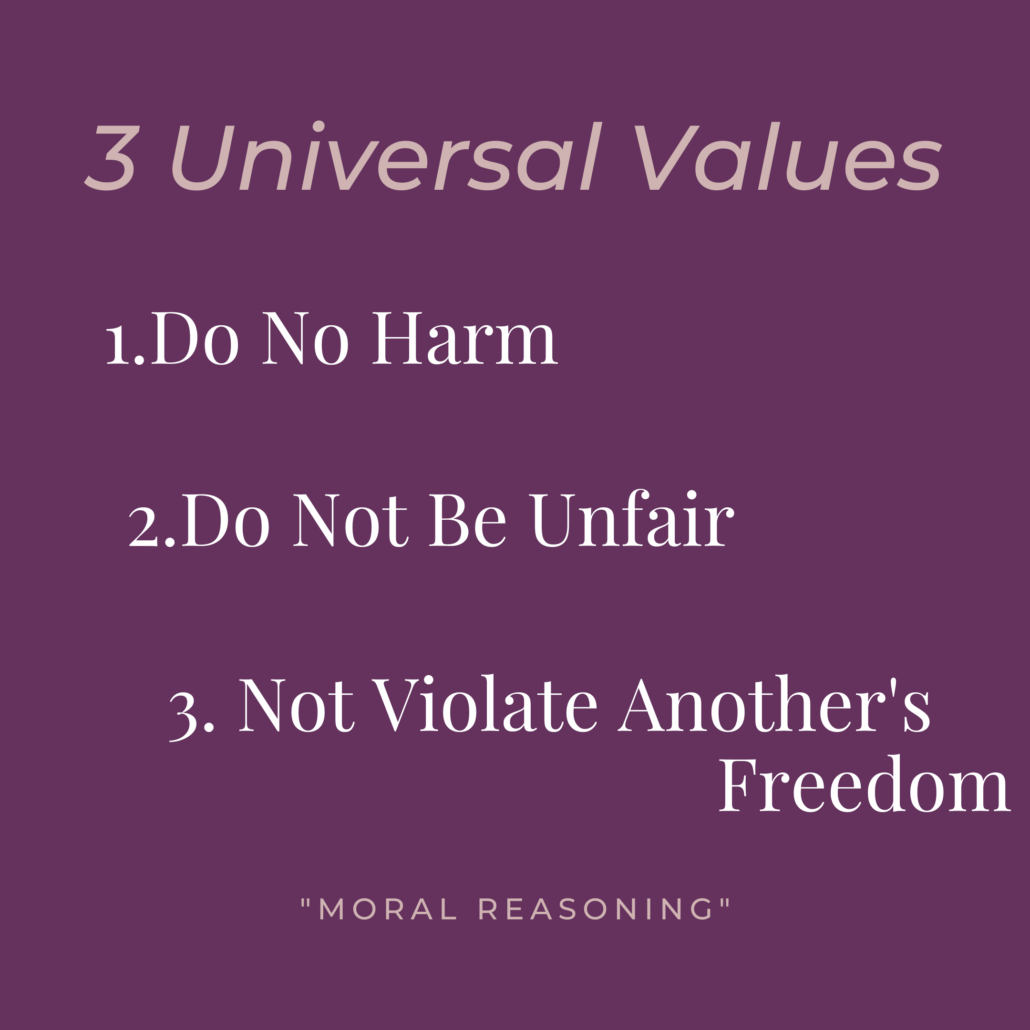

In my teaching, I referenced the work of Joseph DeMarco and Richard Fox and their book “Moral Reasoning.” They write of three universal values that have been accepted in human society across time and geography.

They are:

- Do no harm: We should not harm others. We should not harm ourselves.

- Do not be unfair: Fairness is defined as being judged or dealt with in the same way, by the same rules or standards used in judging or treating others in the same or similar circumstances.

- Do not violate another’s freedom, meaning people should not interfere with another person’s freedom of action. But this value does not condone morally bad acts just because they were freely chosen.

The DeMarco and Fox principles provide a framework for determining if a cause is morally right or wrong or has elements of both. And their application can help us find common ground when dealing with our most troublesome social issues, from issues of religious liberty, to abortion, to gun rights, to the wearing of face masks in the time of Covid-19.

Is there a solution to any problem that minimizes unfairness to stakeholders? That minimizes harm to stakeholders? That protects the freedom of stakeholders?

Managing that sort of calculation requires civil discourse between those who disagree and a willingness to compromise, the hallmark of a civil society.

But as Grant noted some causes are simply and explicitly morally wrong. Issues of racial justice (Black Lives Matter), LGBTQ rights, economic inequality, to name a few, have no countervailing views that can be defended ethically. Yes, those who believe in white supremacy may be sincere in their beliefs. But their cause is morally wrong, violating all three DeMarco and Fox principles. White supremacy is evil. And so supremacy advocates must be opposed at every turn.

In these times, we must separate those absolutes from the more nuanced issues and then find the common ground that represents collaborative compromise, if not consensus. Clearly that is not going to happen on a national scale and not in the halls of government where self-serving political leaders of all stripes have caved to the extremes. But it could happen locally, on a small scale.

What if we could establish a self-generating network of civic discussion groups modeled on those ubiquitous Oprah-inspired book clubs?

One of my closest friends describes a men’s coffee group he enjoys. The group is made up of retirees with a wide range of experiences and a wide range of views. He says their discussions are lively, disagreements often profound. But participants are exposed to the views of those who see the world differently from themselves. There is enormous value in that.

Creating such a network cannot be a role for government. Too much political baggage. Maybe in a neighborhood-based city like Spokane, the official neighborhood organizations could take on the task. Maybe a social-media network such as Next Door could become a facilitator. At one time, it was a role for local journalists.

Back in the halcyon civic journalism days of the ‘90s, the late social scientist and pollster Daniel Yankelovich argued that helping communities work through complex problems and attendant values clashes should be a fundamental journalistic responsibility. He called that journalistic process “working through” and the result a form of “public judgment.” Social scientist Richard Harwood argued that journalists should initiate the community conversations that should be happening but are not.

With so few community journalists surviving the digital revolution and Covid-19 economic collapse it is too much to expect help from that quarter. But if we are going to find our way out of this threatening moment in our civic history, some civic institution must step up.

If you have ideas, please send them to me.