In newly independent America, there was a crazy quilt of state laws regarding religion. In Massachusetts, only Christians were allowed to hold public office, and Catholics were allowed to do so only after renouncing papal authority. In 1777, New York State’s constitution banned Catholics from public office (and would do so until 1806). In Maryland, Catholics had full civil rights, but Jews did not. Delaw, had official, state-supported churches.

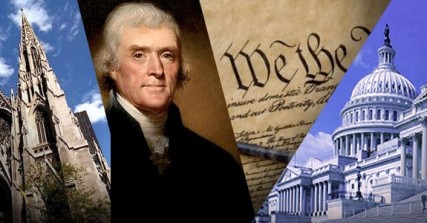

In 1779, as Virginia’s governor, Thomas Jefferson had drafted a bill that guaranteed legal equality for citizens of all religions—including those of no religion—in the state. It was around then that Jefferson famously wrote, “But it does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods or no God. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.” But Jefferson’s plan did not advance—until after Patrick (“Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death”) Henry introduced a bill in 1784 calling for state support for “teachers of the Christian religion.”

Future President James Madison stepped into the breach. In a carefully argued essay titled “Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments,” the soon-to-be father of the Constitution eloquently laid out reasons why the state had no business supporting Christian instruction. Signed by some 2,000 Virginians, Madison’s argument became a fundamental piece of American political philosophy, a ringing endorsement of the secular state that “should be as familiar to students of American history as the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution,” as Susan Jacoby has written in Freethinkers, her excellent history of American secularism.

Among Madison’s 15 points was his declaration that “the Religion then of every man must be left to the conviction and conscience of every…man to exercise it as these may dictate. This right is in its nature an inalienable right.” Madison also made a point that any believer of any religion should understand: that the government sanction of a religion was, in essence, a threat to religion. “Who does not see,” he wrote, “that the same authority which can establish Christianity, in exclusion of all other Religions, may establish with the same ease any particular sect of Christians, in exclusion of all other Sects?” Madison was writing from his memory of Baptist ministers being arrested in his native Virginia.

As a Christian, Madison also noted that Christianity had spread in the face of persecution from worldly powers, not with their help. Christianity, he contended, “disavows a dependence on the powers of this world…for it is known that this Religion both existed and flourished, not only without the support of human laws, but in spite of every opposition from them.”

Recognizing the idea of America as a refuge for the protester or rebel, Madison also argued that Henry’s proposal was “a departure from that generous policy, which offering an Asylum to the persecuted and oppressed of every Nation and Religion, promised a lustre to our country.”

After long debate, Patrick Henry’s bill was defeated, with the opposition outnumbering supporters 12 to 1. Instead, the Virginia legislature took up Jefferson’s plan for the separation of church and state. In 1786, the Virginia Act for Establishing Religious Freedom, modified somewhat from Jefferson’s original draft, became law. The act is one of three accomplishments Jefferson included on his tombstone, along with writing the Declaration and founding the University of Virginia (He omitted his presidency of the United States). After the bill was passed, Jefferson proudly wrote that the law “meant to comprehend, within the mantle of its protection, the Jew, the Gentile, the Christian and the Mahometan, the Hindoo and Infidel of every denomination.”

Comments?