White Christians Think Too Many People See Racism When It’s not There, New Survey Finds

A new survey from Pew Research revealed once again how deeply divided religious Americans are when it comes to matters of race.

Contributions from FāVS from readers like you make this news story possible. Thank you.

News Story by Bob Smietana | Religion News Service

Three years after a national racial reckoning that followed the death of George Floyd — and 60 years after the March on Washington — Americans remain divided on issues of race and discrimination. That’s especially true for religious groups, according to newly released data from the Pew Research Center.

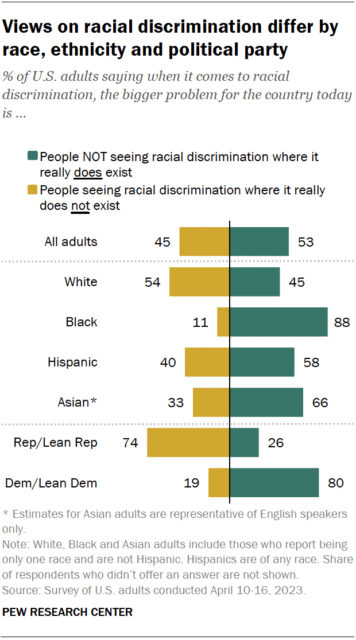

In April, Pew asked Americans which was the bigger problem facing the country when it comes to matters of race: People overlooking racism when it exists or seeing racism in places where there is none.

Overall, just about half (53%) of Americans said people not seeing discrimination where it does exist was a bigger problem. Just under half (45%) said people seeing discrimination where is does not exist is the bigger issue.

Among religious groups, however, white Christians are most likely to say claims about non-existent racial discrimination is the biggest problem, including majorities of white Evangelicals (72%), white Catholics (60%) and white Mainline Protestants (54%), according to data provided to Religion News Service from Pew Research.

Few Black Protestants (10%), unaffiliated Americans (35%) or non-Christian religious Americans (31%) agreed.

Conversely, Black Protestants (88%), non-Christian religious Americans (69%), unaffiliated Americans (64%) and Hispanic Catholics (60%) were more likely to say that people not seeing racism when it exists is the bigger problem. Fewer white evangelicals (27%), white Mainline Protestants (44%) and white Catholics (39%) agreed.

While a majority of unaffiliated Americans, also known as Nones, say that not seeing racism is the bigger problem, there were differences when it came to race, according to Pew.

“Among White unaffiliated adults, 61% say people not seeing racial discrimination where it does exist is the larger problem for the country, while 39% say the opposite,” a Pew spokesperson said in an email. “Among Non-White unaffiliated adults, 71% say overlooking racial discrimination is the bigger issue, compared with 29% who give the opposite answer.”

Divides over issues of race have heated up among American Christians in recent years, as the so-called woke war has pitted those who do believe systemic racism is an ongoing issue against those who don’t. That divide has fueled conflicts in the Southern Baptist Convention and other evangelical groups, led to feuds in local churches and Christian colleges, become a major debate during school board meetings and been a major talking point in the current race for U.S. president. The issue of race also led to concerns about the rise of white Christian nationalism in churches.

Pew’s study suggests those divides are unlikely to go away.

Overall, more than half of White Americans (54%) said people seeing non-existent racism was the bigger problem. Eighty-eight percent of Black Americans, along with 58% percent of Hispanic Americans and 66% of Asian Americans, say people not seeing racism when it exists is the bigger problem.

Most Republicans and those who lean Republican (74%) said that people seeing non-existent racism is a bigger problem, while 80% of Democrats say the bigger problem is people not seeing racism that exists.

A similar survey in 2019 found that 57% of Americans said that not seeing racism is the bigger problem, while 42% said that seeing non-existent racism is the bigger problem.

George Yancey, a professor of sociology at Baylor University, said that other surveys have shown similar divides when it comes to matters of race and discrimination, adding that attitudes changed little even after the protests that were sparked by the death of George Floyd.

Yancey said that churches have done little to resist the influence of politics among their members. “We have taken our overall polarization and we place it into the racial debate,” he said. Politics, rather than their religious beliefs, shape attitudes about race.

He believes similar approaches happen among more progressive religious people, and as a result there’s little listening going on when people talk about matters of race. “I don’t think Christians are the source of polarization,” said Yancey. “But I do think we have not fought against it. We have accepted in and put it into our ministries rather than trying to show concern and care for people who disagree with us.”

Sociologist Michael O. Emerson, who studies religion and public policy at Rice University and co-wrote “Divided by Faith,” an influential 2000 survey of religion and race in America, suspects the trouble is more than politics. In a new book, “The Religion of Whiteness,” due out in the spring, Emerson said he and his co-author argue that the idea of being colorblind — disregarding race as having any impact on life — has become theological.

“It’s not just a ruse for politics,” he said. “It is theological. It is a transcendent reality.”

Emerson said that the religion of whiteness — a distinctly American faith, he said — has a number of symbols, including a white Jesus, the cross, the American flag and firearms. “The only way to address this is a spiritual battle,” he said. “You can’t just use politics to change it.”

Derwin Gray, pastor of Transformation Church outside of Charlotte, North Carolina, and author of “How To Heal Our Racial Divide,” also worries about how race and religion have been intertwined. In recent years, he believes it has become increasingly difficult to talk about matters of race in churches.

“Race and prejudice are a matter of idolatry in the American church,” said Gray. “As a pastor, I have to gospel that out of people.”

Gray said that almost every country in the world has issues of race, because human beings are by nature sinful. So, America is not unique in having to deal with the issue of race.

He said that the growing number of multiethnic churches shows that racial reconciliation can take place. About 1 in 4 congregations in the U.S. is multiracial, according to the 2020 Faith Communities Today study.

But being multiethnic means more than just people from different backgrounds worshipping together, said Gray. It also means multiethnic leadership and listening across political lines.

In his book about racial reconciliation, Gray recounts talking with a fellow Christian leader who argued that systemic racial injustice does not exist. Instead, the leader saw American media outlets as organized efforts to discriminate against American Christians.

Gray said that most of the folks who come to Transformation Church, a multiethnic congregation of about 10,000, embrace the idea of racial reconciliation and are open to dealing with America’s racial history. But not all — and those folks often don’t stay, he said.

“If we are truly allowing Jesus to shape us, and we’re truly growing in grace, we’re going to desire the best for our brothers and sisters,” Gray said. “We’re not going to deny the impact of the past. We’re not going to live in the past. We’re going to join hands together to move forward to a better future.”