What Totem Poles in Alaska Taught Me about Appreciating Other Cultures

Please consider donating to the FāVS Fund for Social Justice Reporting

Commentary by Walter Hesford | FāVS News

During a recent small-ship cruise up Alaska’s Inland Passage from Sitka to Juneau, my wife and I saw many totem poles, both old and fairly new. Since we were voyaging through Tlingit territory, we paid special attention to those witnessing to Tlingit culture. Fortunately, we had a Tlingit as our guide.

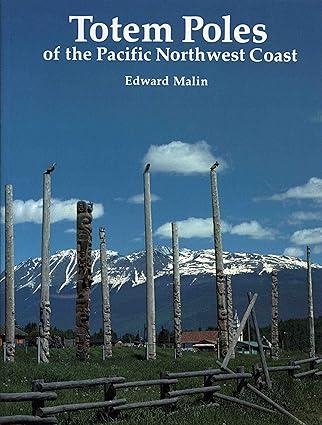

Before I left for our Alaska trip I read Edwin Malin’s 1986 “Totem Poles of The Pacific Northwest Coast.” Malin, an anthropologist who studied totem poles for more than 40 years, speculated that the Tlingit had been crafting short interior house posts, memorial poles and mortuary poles for generations before European contact.

The construction of tall totem poles, according to Malin, spread north from the Haida people and was made possible by the introduction of European tools.

Our Tlingit guide, however, posited that the size of the totem poles was determined by the size of the trees (generally red cedar) available, which slowly assumed greater height after the last ice age.

A Tlingit elder who spoke to us in the small town of Kake while standing by one of the world’s tallest modern totem poles said that that his people have been erecting poles since “time immemorial.”

How the Term ‘Totem Pole’ Evolved

The word “totem” is not Tlingit, but a 1760 English adaptation of an Algonquian word signifying kinship group. It evolved to mean an animal or natural object emblematic of a family or clan.

“Totem” plus “pole” was first used by English traders in 1808 to describe what they were seeing along Alaska’s southeast coast.

Though a term developed by outsiders, totem pole does capture an aspect of these remarkable cultural artifacts confirmed by our guide and by information gleaned at two wonderful places we visited in Sitka, the home of Kiksadi Tlingit 8,000 years ago.

Visiting Totem Pole Sites

The first, the Sitka National Historical Park, offered a totem pole trail through the woods and along the harbor side. The poles on this trail were awesome but not specifically Tlingit.

Inside the park’s visitors’ center, however, there was much about how and why Tlingit clans and families constructed poles to honor leaders or commemorate potlatches and historic events, linking leaders and events to totemic animals and important myths. And by myth, I mean not an untrue story, but a story that reflects and fosters the beliefs of a people.

We also visited the Sheldon Jackson Museum that contained native art and artifacts gathered from all over Alaska, including beautiful beaded regalia created by our guide’s grandmother. Sheldon Jackson, a Presbyterian missionary, began collecting the items on display 1877, realizing their value and the need to preserve them.

Sheldon Jackson’s Role Preserving Native Culture

Jackson was a rarity among missionaries. Many missionaries held native cultures in little regard and specifically opposed totem poles and their creation, rightly seeing them as witnessing to native myth they wished to replace with Christian myth.

American missionaries also wanted to end potlatches during which totem poles were often erected. In these potlatches important families showed their wealth by distributing it to all who attended. How un-American!

Traders and colonists also undermined totem pole culture by destroying the economy and environment upon which the native people depended. By the late nineteen-century, multitudes of decaying totem poles along the coast witnessed to the abandoned villages that once thrived there.

Ironically, missionaries such as Jackson — along with other non-native people often interested in collecting specimens for museums — who began the effort to preserve totem poles. The native peoples themselves initially had little interest in this preservation effort, as the totem poles had served their purpose.

Cultural Differences Appreciated

This witnesses to an attitude toward art that differs from that of Euro-Americans. For the Tlingit, art is always functional, finding its value and meaning within its culture.

By the twentieth-century, some native folk realized the need to keep alive the traditions of creating totem poles to train young artists in the difficult practice of carving and painting them. The Sitka National Historical Park exhibited a totem poem being created by Tlingit artists. Their work witnesses to the resilience of Tlingit culture.

On the totem poles we saw I could recognize the stylized representations of clan leaders, of animals such as bears, eagles, salmon, orca and frogs, along with the myths that connect the human to natural and supernatural worlds.

One myth is of Raven, the Tlingit trickster, who rescued the sun from captivity and carried it to the sky in his beak. Our guide said that this might reflect the time when the sun was hidden by volcanic ash for a long period.

There is much we don’t understand. More specifically, I realized on this trip that there is much about Tlingit culture I don’t understand. The totem poles witness to my ignorance.

It is good to realize that we can’t readily understand a culture that radically differs from ours and we can learn to respect and appreciate our cultural differences.

Such a great article and history of the totem pole. I’ve been inspired by traditional cultures to make small steps in commemorating life events with blessings, art and craft, instead of just another party. It’s completely non-European but I’m enjoying the slow journey and the connections it creates. Thanks again to the author and to FAVS for such meaningful content.

Thank you NancyJ!

Excellent and thought-provoking article! I appreciate your offering the broader definition of “myth” because for every people, their myths are lifegiving to the people in their respective spiritual modalities.

Perhaps we would be amiss to speak of the Tlingit Raven as a literal corvid just like African and Eurasian deities have had associations and identities with certain animals, yet are not those animals. That even includes Isis, associated with the kite (bird not toy). There is the Egyptian myth of Isis who gained the power of the Sun god, Ra, by fashioning a venomous serpent from his spittle. Isis was able to heal, but not without him telling her his name. It was a trick, much like the way Raven played the trickster upon the Sun in the Tlingit myth. Yet the trick Isis pulled had a practical element in the healing process, for to connect with the Ra to be healed, knowing his name was essential. Seeing these mythic comparisons between these dissimilar cultures, I wonder whether there may have been a volcanic event that influenced the narrative surrounding Isis and Ra… perhaps the eruption of Thera?