This is part 5 in a series. Read the previous post here.

It’s been reported that the more we defend our beliefs, the more entrenched our beliefs become. We typically do not change our minds, though research indicates that religious belief decreases with analytical thinking.

All of us can relate to encountering someone with different beliefs, especially religious or political, which in turn causes us to feel threatened. Suddenly, the part of the brain tied to emotions becomes activated. We cannot resist the urge to defend ourselves, our stances.

This biological response may explain why it is so easy to slip into right-wrong thinking, fueling our desire and attempts to convert others to a particular way of believing. We go about our lives as if human ‘being’ and human ‘believing’ are one in the same. What a conundrum. I wonder though, are we really our beliefs?

In this final segment, I take up again the conversation of transcending personal beliefs to understand each other. Not to abandon what we believe but to take a stand for our convictions while honoring the convictions of others.

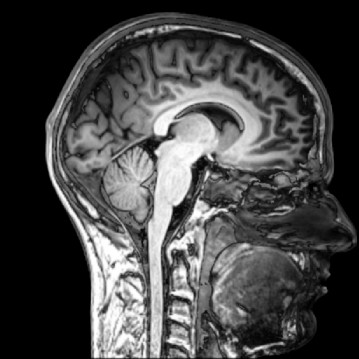

One promising place for dialogue and working out a theology of understanding is the field of neurotheology. From Laurence McKinney’s exploration of the idea that the brain creates religious interpretations to answer questions like “where did I come from” and “where am I going” (Neurotheology: Virtual Religion in the 21st Century,1994), to Andrew Newberg’s brain scans of praying nuns, monks and Pentecostals speaking in tongues, neurotheology showcases collaborative efforts on the question of God and the brain, and whether religious experiences originate in the brain or are external phenomena that remap the brain.

More work is needed, especially in determining how the brain acquires religious beliefs and the language to express those beliefs. This is where linguists and philosophers and psychologists can enter the dialogue, like Noble winner in economic sciences, Daniel Kahneman, and his research on the two systems of the brain (Thinking, Fast and Slow, 2011).

Such an interdisciplinary approach has the opportunity to bring awareness to the linguistic and theological barriers that divide us — the Christian belief in Jesus as the incarnate Son of God; the Mormon belief in Jesus as the literal Son of God; the centrality of the Arabic language for the Quran and daily worship prayers (Salah) and Allah as the supreme being and creator of the universe for Muslims; Yeshua as the Messiah for Messianic Jews; YHWH as the one true G-D in the Jewish tradition.

At the start of this series, I told a story involving a discussion of prayer with two former students with very different backgrounds, one an agnostic, the other a devoted Muslim. Not long after this prayer episode in my office, these two students returned to my office. The one from Pakistan brought a text. He pointed to a passage that urged Christians to rid themselves of the notion of the Trinity. Perceiving this to be an attack on my Christian stance, I felt my heart rate go up. As Newberg said, when we confront someone who believes differently than we do, it activates the limbic system, the part of the brain responsible for emotional response. To transcend the divide and stay in relationship with my student, I realized the necessity to take a stand and remain true to my Trinitarian convictions while understanding the importance of his belief in the sacred oneness of Allah.

Interestingly, many people report acquiring their religious beliefs based on the religion they were born into. They tend to stay with the same religion, but not without questioning their parents’ beliefs and arriving at their own understanding after thinking it through for themselves. Others report falling away from religion. Then some major life event has led them back, though not necessarily to the same religion or church they adhered to before.

One thing stands out as people open up about the very personal, first-hand experiences and encounters that have shaped their beliefs: the need to feel understood and that they matter. Perhaps herein lies the distinction I’ve been searching out. Our vulnerable selves find a home, a sense of belonging, when our beliefs or ideologies are validated yet not reduced to who we are.

The scariest thing happens when we feel truly understood and understand another: a change of mind.

Fascinating article! I’m interested to hear what a multi-disciplinary approach brings to the study of how we acquire belief.

Thanks, Bruce. Neurotheology comes the closest that I’m aware of, leaving plenty of room for more interdisciplinary work!