(Based on a paper I presented in May 2012, titled “Ways of Believing,” at the regional meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature, Concordia University Portland)

The phone rang. Upon answering, my dad was on the line to ask a question that, coming from him, took me by surprise. “What do you know about Calvinism?” Before I could respond, I heard my dad say, “Here is my daughter.” Shortly, I was on the phone with one of his paint contractors.

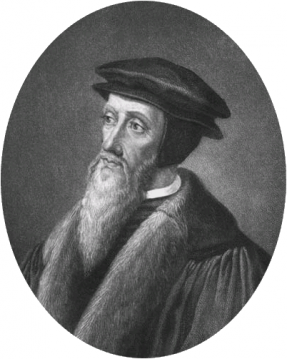

For nearly an hour, the contractor shared his struggles with the church he has attended for some 30 years. New leaders have been putting together a faith statement with tenets from strict Calvinism on election, predestination, and salvation. Simply put, and bothersome to the contractor, his church’s stand on who is in and who is out.

The contractor has disagreed with the stance taken recently by the church leaders. He feels a pull, wanting to align his beliefs with what the Bible, not his church, teaches. He feels pressure to believe a certain way, or else.

Conflict hurts. At one point during our conversation, the contractor broke down. I fear his dilemma is widespread. It goes something like this: will I be accepted in the church if I disagree, if I have questions?

I wonder if this scenario reflects a deeper issue, revealing the tendency to confuse who we are as human beings with our beliefs. To what extent, if at all, are we our beliefs?

I pick up where I ended in the third post for this series on the need to transcend one’s beliefs to embrace the humanity of self and of another. I called attention to the philosopher John Searle and his theory of the five basic ways humans use language, and that language arises from mental states in the brain (e.g., my ability to assert that it is raining arises from my belief that it is raining; my ability to direct you to listen arises from my desire for you to listen, etc.).

In working directly with Searle for my research (applying his philosophical categories to the New Testament writers and what they asserted/believed concerning Christ’s blood), I was intrigued with Searle’s lack of belief in God. For Searle, belief in God goes against the natural order of how the world works. It is misleading to label Searle an agnostic or atheist. The reason, he says, is that he has moved “beyond atheism.” He has moved away from religious dialogue because for him it is pointless.

I can appreciate what the contractor has been going through. Working with a non-religious philosopher for my religious project produced for me questions and vulnerability. But I continued to read Searle’s books. We met. We corresponded. He coached me, I a Christian, he a nonbeliever.

As time went on, I became curious how Searle reconciles his biological naturalism with the fact that many, if not all, people have some religious experience or thought at some point in life. One day, I mustered the courage to ask him. True, says Searle, people do have supernatural experiences, but “from individual experience, nothing much follows.”

Conversation closed. An impasse develops that fast.

But is this really the end of the conversation, or does Searle’s comment reflect the tendency to stay within the familiar confines of one’s particular field of study (i.e., comfort zone), missing opportunities for an interdisciplinary approach — scientists, theologians, psychologists, and philosophers — to tackle the nature of divine experiences, religious beliefs, and the language to express them? All processed in and by the brain. Here, as we will see, the field of neurotheology looks promising.

I keep before me my acquired belief in Jesus. More pressing, I keep in mind the contractor and Searle as reminders of the way our different beliefs split us into the realm of right-wrong.

Faith and belief should be personal and each person should not ever believe what someone else tells them but to research, study, meditate, pray, fast etc. Throwing out what is not proven, what is paradigm, and opinion and embracing according to one’s understanding after much of using the above mentioned methods embrace and hold on to what they find is right and truth for them. Even if it means going against popular opinion or laws of the land or rules and regulations imposed on them by society. Being true to what you understand and know is the crux of faith and not letting anyone or thing shake it. However most people are content to let other’s tell them what to think, believe and are often shallow in their belief and can be shaken. Especially when challenged and they cannot back it up with fact from several sources be it history, science or religion or all combined. For me God is and has always been and shall always be and I have walked out of several churches that are like a hammer, or it is one big social club or feel good church but there is no substance or meat to them. I was raised with a mixture of beliefs and found many were lies or half truths. So I take what I know is true and move on to deeper concepts through study and testing and research and prayer and mediation and even at times fasting. I answer to no man or woman but to God alone and Christ is my savior. He is my high priest, my shepherd, my King, My Lord of Lords and my older brother. I have been through a lot of sorrow, hurt, loss, disappointment and my faith has got me through, become stronger and is not shaken.

Celanith, when you say “Being true to what you understand and know is the crux of faith and not letting anyone or thing shake it.” and “I answer to no man or woman but to God alone and Christ is my savior. He is my high priest, my shepherd, my King, My Lord of Lords and my older brother.”

It sounds like you are saying that you have absolute certainty about the validity of your beliefs. Is that right?