We had never met, though I recognized him when he came for me at our arranged time. Shorter than I, he stood about 5 feet tall, gray and hunched over. Attempting to sharpen my pencil in an old sharpener bolted on a ledge opposite the checkout counter, he saw my difficulty, grabbed the pencil out of my hand, and placed it in the sharpener. He manipulated the pencil in various positions as a therapist would a limb, refusing to give up.

In the end, he had no more luck. After mangling my pencil, he handed it to me and said, “Hi. I’m John. I think you’re here to see me. Come.” He led me to his office with a shuffle, carrying my backpack.

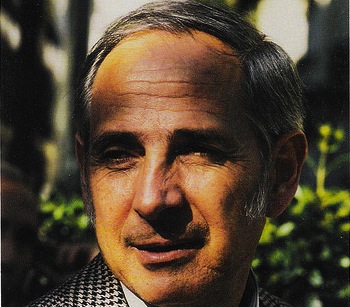

In a quaint philosophy library on the UC Berkeley campus, in June of 2005, this was my initial encounter with the contemporary speech act theorist, John R. Searle.

I already knew Searle’s theories of language and mind. His books had covered my kitchen table and dining room floor for the past year. I had handwritten notes of his trilogy of works, Speech Acts, Expression and Meaning, and Intentionality. My whole existence consisted of reading and re-reading his books and articles while taking notes.

Here we sat face-to-face, all because I had written him explaining my research on bridging two distinct disciplines of speech act theory and biblical interpretation of the blood-of-Christ motif. He wrote back saying that I had an interesting set of problems, and that we should meet.

In Searle’s office, with his research assistant at the computer yet listening in, paranoid about catching my cold because she was taking immune-system suppressing drugs after a kidney transplant, my quirky conversation with Searle went something like this:

Searle: “OK. What’s your question for me?”

Lace: “For starters, I’ve been reading up on how biblical scholars and theologians are using speech act theory. In my opinion, they seem to be misrepresenting your theories, and …”

Searle: “That’s because they probably are. So what’s your question for me?”

Lace: “I’ve read your books. I’m wondering whether your categories of language and mind can be applied to the biblical writers.”

Searle: “If no, then something is wrong with the categories. If the categories are good, then they apply.” (Later in correspondence, Searle clarified, “I do not wish to imply that I am endorsing the accounts of the biblical writers. The point is simply that the categories are intended to be perfectly general and should apply across any kind of discourse”).

Lace: “I’m trying to figure out how to apply your categories to certain New Testament passages so I accurately represent your theories as well as what the biblical writers wrote…”

Searle: “You’ve got my theories down. Now the biblical material, I can’t help you with that because I know nothing about the Bible.”

Lace: “Alright.”

Searle: “So what’s your question for me?” (He begins to fidget with his camera).

Lace: “I guess I’m not sure.”

Searle: “I’m going to lay down on the couch and take a nap. You go and think of a question and come back when you have one.”

Before I had left his office, Searle was lying down, eyes shut. I closed the door and returned to the philosophy library. I brainstormed ideas for that one dynamite question that would make my trip to Berkeley, and Searle’s time, worthwhile.

An hour later, I returned to Searle’s office, though I cannot recall with what question. His research assistant sat in the same spot. Searle made room for me on the couch.

Searle: “So, what’s your question for me? By the way, have you read Habermas? He’s been pissing all over me lately.”

Lace: “No, except for his article in John Searle and His Critics.”

The conversation dwindled, never getting off the ground. I flew home the next day feeling simultaneously stupid and confident — stupid over my inability to ask that one meaningful question, confident to apply Searle’s theories to my New Testament data.

In my next post, part three in the series of transcending personal beliefs, I will present Searle’s theories of language and mind.