The National Christmas Tree turns 100 this year. Here are five faith facts to know.

Though the tree has not been lit every single year across the century, it is the second-oldest White House tradition after the Easter egg roll.

News story by Adelle M. Banks | Religion News Service

It was Christmas Eve in 1923.

A church choir sang, Marine band members played and the president of the United States pressed a button to light the first National Christmas Tree under the gaze of thousands of onlookers.

For 100 years, the tree has represented a symbol of civil religion as Americans mark the Christmas season.

Yesterday (Nov. 30), President Joe Biden did the honors just as President Calvin Coolidge did at that first lighting, and contemporary gospel singer Yolanda Adams sang for the crowds gathered on the Ellipse in the shadow of the White House.

Though the tree was not lit from 1942 to 1944 — due to the Second World War — it is the second-oldest White House tradition, after the Easter Egg Roll, which began in 1878.

“A hundred years is a fairly significant milestone to reach for consistently practicing a tradition,” said Matthew Costello, senior historian of the nonprofit White House Historical Association. “This is really part of the customs and the traditions of the White House and living in the White House.”

Whether the tree will continue as a symbol of civil religion — a Christian tradition, yes, but also a generic celebration of the holiday known for Santa and reindeer — is an open question, said Boston University professor of religion Stephen Prothero. In the wake of the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol, the tree’s intersection of politics and religion may be seen as too fraught.

“At this point, these Christian symbols in the public square feel very different to me and to many other Americans, than they have in the past,” he said. “And that’s precisely because of the increasing power of white Christian nationalism in American society.”

Already, the tree can seem like a relic of an America that is now past. “You would think, based on separation of church and state, that the federal government wouldn’t get into the Christmas tree business, but we have been doing these kinds of things for a long time,” Prothero said.

But the tree has always been part of America’s balancing act of alternately welcoming or rejecting religion in the public square. “It used to be that there was a kind of a gentleman’s agreement — and I say, gentleman on purpose, because it was men who were making this agreement — and the agreement was that you could have religious symbols in the public space, but that they would have to be generic, that they wouldn’t be explicitly Christian.”

Here are five faith facts related to the National Christmas Tree:

1. It’s been a place for God-talk by Democrats and Republicans.

In 1940, before the U.S. entered the conflict in Europe, Franklin D. Roosevelt used the tree lighting to condemn the war, referring to the Beatitudes of Christ, and urging “belligerent nations to read the Sermon on the Mount,” a National Park Service timeline notes.

In 1986, Ronald Reagan offered a different interpretation of the holiday. “For some Christmas just marks the birth of a great philosopher and prophet, a great and good man,” he said. “To others, it marks something still more: the pinnacle of all history, the moment when the God of all creation — in the words of the creed, God from God and light from light — humbled himself to become a baby crying in a manger.”

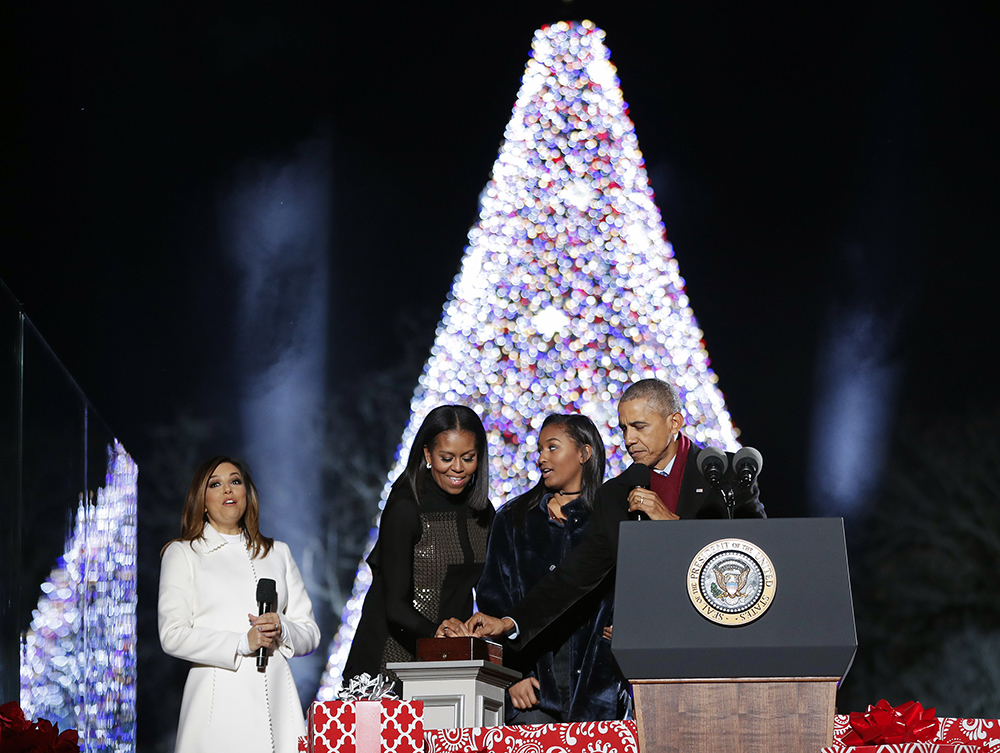

More recently, Barack Obama, referring to baby Jesus, said at a 2010 ceremony that “while this story may be a Christian one, its lesson is universal.”

Donald Trump said in 2017 that the “Christmas story begins 2,000 years ago with a mother, a father, their baby son, and the most extraordinary gift of all, the gift of God’s love for all of humanity.”

2. The Christmas tree was joined by other symbols of faith.

At times, there has been a Nativity with life-sized figures near the National Christmas Tree. An Islamic star-and-crescent symbol also made a 1997 appearance on the National Mall not far from the White House but it was vandalized, losing its star.

“This year for the first time, an Islamic symbol was displayed along with the National Christmas Tree and the menorah,” said President Bill Clinton that year in a statement. “The desecration of that symbol is the embodiment of intolerance that strikes at the heart of what it means to be an American.”

A public menorah first appeared near the White House in 1979, when President Jimmy Carter walked to the ceremony in Lafayette Park. The candelabra moved to a location on the Ellipse in 1987, and a 30-foot National Menorah has continued to be lit annually as a project of American Friends of Lubavitch.

3. Its lighting continued amid difficult times.

Roosevelt lit the tree weeks after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill standing behind him.

After the Nov. 22, 1963, assassination of President John F. Kennedy, his successor waited until a 30-day mourning period was over before lighting the tree. “Today we come to the end of a season of great national sorrow, and to the beginning of the season of great, eternal joy,” said Lyndon Johnson on Dec. 22 of that year.

A few months after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, President George W. Bush rode in a motorcade to the nearby Ellipse for the ceremony.

Costello contrasted these “people-oriented” instances to the more “policy-oriented” rhetoric of State of the Union speeches.

“We see after these moments of national catastrophe, disaster, tragedy, where this can be a really uplifting time for presidents to deliver a message directly to the American people, to remind them about what the season is all about, but also forward-looking,” he said.

4. While it’s kept its name, others have switched to “holiday.”

The neighboring Capitol Christmas Tree was a Capitol Holiday Tree for a time. It reverted back to the “Christmas” title in 2005.

“The speaker believes a Christmas tree is a Christmas tree, and it is as simple as that,” Ron Bonjean, spokesman for House Speaker J. Dennis Hastert, told The Washington Times that year.

Matthew Evans, then landscape architect of the U.S. Capitol, told Religion News Service in 2001 that the tree is “intended for people of all faiths to gather round at a time of coming together and fellowship and celebration.”

Around that time, some state capitols and statehouses also opted to name their pines, firs and spruces “holiday trees” instead.

But the National Christmas Tree has retained its longtime imprimatur.

5. The tree ceremony is really about kids.

An ailing 7-year-old girl asked that President Reagan and first lady Nancy Reagan grant her “Make a Wish” program request that she join them for the tree lighting in 1983.

“The Christmas tree that lights up for our country must be seen all the way to heaven,” Amy Bentham wrote to the program, according to the NPS website. “I would wish so much to help the President turn on those Christmas lights.”

The Reagans granted her wish.

“The bottom line is what the president says and does, it matters; obviously, people listen,” Costello said. “But really, this is about kids, it’s about children and sort of the magical time of the year. And that was just one example, I think, that was especially poignant about why the ceremony matters.”