Spokane’s Haitian community struggles with looming deportation

News Story by Elena Perry and Orion Donovan Smith | The Spokesman-Review

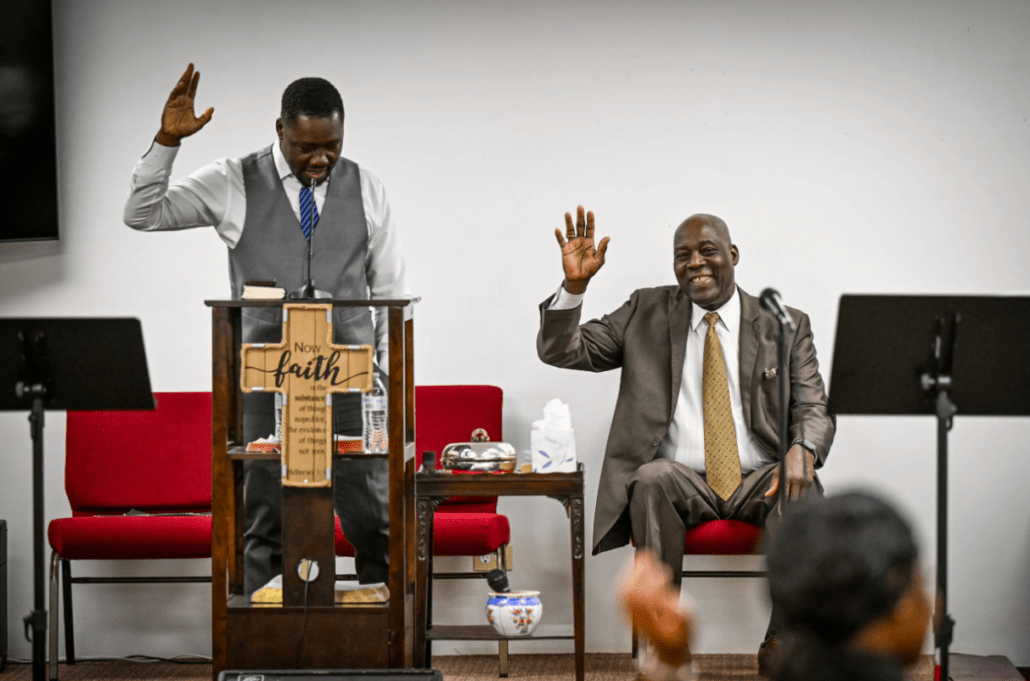

The congregation at Maranatha Evangelical Church in East Central was smaller than usual when the Rev. Luc Jasmin Jr. rose last Sunday to address his flock about a somber subject.

Some members of Spokane’s Haitian community had stayed home out of fear because they already knew what the pastor’s daughter, Katia Jasmin, was about to tell the 20 or so people in the pews. Three days earlier, the Trump administration had cut short a program that has allowed people from Haiti to live in the United States lawfully since 2010, when an earthquake devastated their island nation.

When the pastor’s daughter explained that Temporary Protected Status for Haitians would end on Aug. 3, the congregants began crying and murmuring in Haitian Creole, their shoulders shaking in a mix of tears and anxious, incredulous laughter.

“God is good, God has a plan for us,” Rev. Jasmin reassured his congregation. “There is no reason to cry.”

In the nearly four decades since Congress last made a major update to U.S. immigration law, presidents have repeatedly used their authority to grant Temporary Protected Status, or TPS, to let citizens of dangerous or unstable countries live and work in the United States until conditions in their homelands improve.

Haiti is one of 17 countries currently designated for TPS, with people from four other countries eligible for a similar protection called Deferred Enforced Departure. In a news release announcing the decision to rescind the Biden administration’s extension of TPS, the Department of Homeland Security estimated that more than 520,000 Haitians are currently eligible for the program, but according to the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service, as of September 2024 only about 200,000 were approved for the status, which requires recipients to apply for renewal each time a president extends it.

“Temporary Protected Status is always something that folks live delicately with, because it’s not permanent,” said Mark Finney, executive director of Thrive International, a Spokane-based nonprofit that supports immigrants in the Northwest.

“Generally, you can count on an American president to keep the status in place as long as the country of origin is not safe to return to, either because of military conflict, unstable government or lack of infrastructure from natural disasters,” he said. “In this case, it appears that the current administration is less concerned about providing the protection for folks who literally can’t live back in the countries that they came from, and so a lot of folks are really scared.”

In the complex patchwork of U.S. immigration law, people who qualify for TPS also may be eligible for other paths to legal status, such as requesting asylum, which requires proof of a more specific threat, said Colleen Putzel-Kavanaugh, an analyst at the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute. That can confer what she called a “liminal status” while applications are reviewed, but if they have no other protection in place, Haitians could be subject to deportation when TPS ends in August.

Much of the sermon delivered by the Rev. Jasmin surrounded the fear of deportation. He preached in English while his brother Claude Jasmin, the church’s music director, translated his words into Haitian Creole from his piano.

Rev. Jasmin, who is now a U.S. citizen, shared his own story of coming to the country at age 16 with his brothers and sisters, working to support family in the United States and abroad, all the while praying for stability for his family in Haiti. He implored his congregants to be patient and keep an unwavering faith while their status in the United States is upended.

“I prayed to the Lord, I am going to be free. Free to talk, free to walk, free to praise the Lord,” Rev. Jasmin said, to a chorus of “amens” from the congregation.

Katia Jasmin, who serves as executive director of the advocacy and support group Creole Resources, estimated that there are roughly 500 Haitians in the Spokane area, many of whom rely on TPS to live and work legally in jobs in the region. She said the fear of being sent back to their home country weighs heavily on the community.

Joel Dumesle, a U.S. Army veteran who became a U.S. citizen after immigrating from Haiti in the 1990s, works in Spokane as a social worker and said members of the local Haitian community who aren’t at risk of deportation still feel unsafe because of the Trump administration’s move to end TPS. He has nine family members in the United States with various legal statuses, unsure of what’s next but dreading that it means returning to Haiti.

“Even the people who had homes, they’re either burned down or are really just not safe,” Dumesle said of his relatives in Haiti. “I think all of us have the same fear.”

Phamania Dalcima held back tears during the service. The 21-year-old, who goes by Phanie, has been in Spokane for almost a year on TPS, living with Katia Jasmin and working at the Jasmins’ Parkview Early Learning Center while studying English at Spokane Community College. Once she passes English language classes, Dalcima said, she hopes to study sonography and become an ultrasound technician.

“The use of TPS, historically, has been for these large groups of people who may not qualify for some other sort of status, but certainly can’t be returned to their country of origin, even if they’d like to go back, because of the conditions there,” said Putzel-Kavanaugh. “There’s not a real alternative for people, unless they fall into one of those narrow categories of either being able to apply for asylum or having a family member to sponsor them, or qualifying for some other visa form.”

The protection applies to people from a designated country whether they entered the United States legally or not. In recent years, Haitians have arrived lawfully through several programs, including a recent one that allowed U.S. volunteers to sponsor immigrants from Haiti, Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela.

Haiti occupies the western half of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, named by Italian explorer Christopher Columbus when he landed there in 1492. Three centuries later, in 1804, Haiti became just the second independent republic of the colonial era – after the United States, where Columbus never set foot – when enslaved Haitians revolted against French rule. But beginning in 1825, under threat of a naval invasion, France forced the newly free people of Haiti to compensate the French government and French slaveholders, an “independence debt” that totaled roughly $21 billion in today’s dollars by the time the payments ended in 1947.

The United States has also played a part in making Haiti the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere. Although Haitian troops helped U.S. forces defeat the British during the Battle of Savannah in 1779, the U.S. government refused to recognize Haiti’s government until 1862, isolating the world’s first Black-led republic for nearly 60 years.

After Haiti’s president was assassinated in 1915, the United States invaded the country and occupied it until 1934. U.S. troops intervened in Haiti again in 1994, after the nation’s first popularly elected president was ousted in a coup.

Following the earthquake that killed more than 100,000 Haitians in 2010, the country slid deeper into dysfunction and violence, culminating in the assassination of another president in 2021. Since June 2024, a Kenya-led security force backed by the United Nations has been battling the gangs that control much of Haiti, which have overpowered Haitian police with the help of black-market guns from the United States.

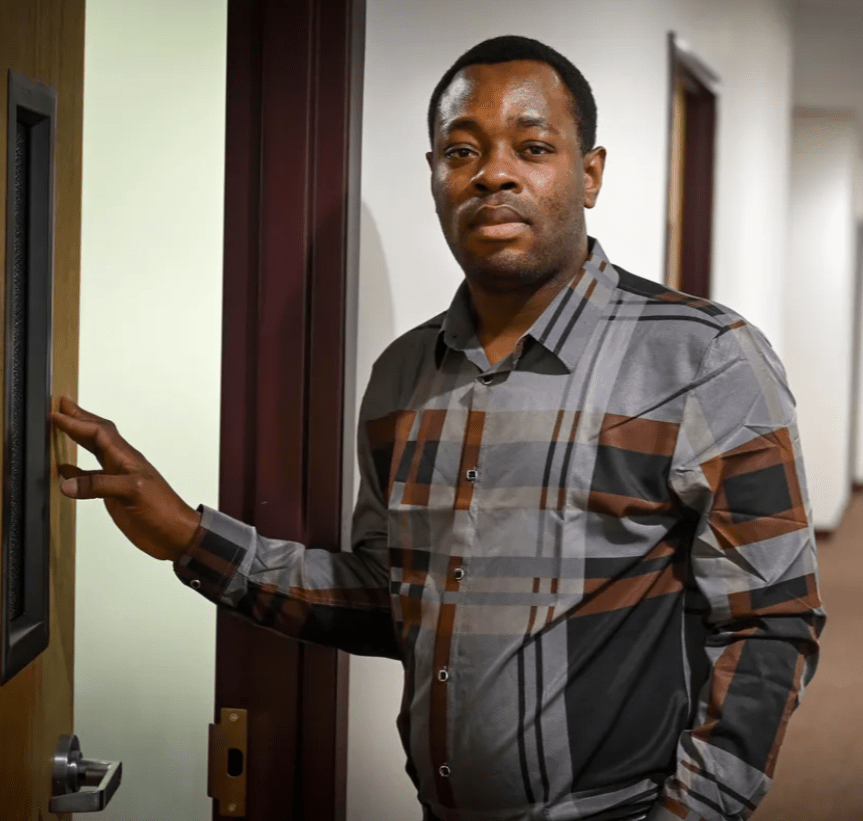

Claudnel Jean-Baptiste, a Haitian immigrant who studied medicine in the neighboring Dominican Republic before coming to Spokane in 2023 and finding work in a warehouse, said going back to his home country would amount to a death sentence.

“There are no opportunities for the youth or for the elders. It’s fighting all the time, gangs killing innocent people,” he said through a translator. “The gangs have no pity for babies, pregnant women, nobody. In reality, there is no life, it’s hopeless. People are staying because they have nowhere to go for refuge. It’s a daily struggle.”

Jean-Baptiste applied for TPS after entering the country with parole, which allowed him to get work authorization.

“The paperwork is still good until May, but once May comes, I have no idea what to do,” he said, adding that the news of TPS ending so soon left him feeling “dead.”

Working in Washington state has allowed Jean-Baptiste to send money to his family in Haiti and the Dominican Republic, the two countries that share a roughly 30,000-square-mile island split by a border drawn when France controlled its west and Spain ruled the eastern half.

“Even if it is my country, I have no desire to go back and I don’t see how or why I would go back, the way things are,” he said. “The way things are in Haiti, anybody who stays there, it’s because they don’t have the opportunity to leave the country.”

TPS is meant to last until conditions in a given country improve, but when Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem announced that the program would end in August – rescinding a decision by her Democratic predecessor to extend TPS for Haiti until February 2026 – she didn’t make the case that Haiti is safe. Instead, the department said the move is “part of President Trump’s promise to rescind policies that were magnets for illegal immigration and inconsistent with the law.”

“We are returning integrity to the TPS system, which has been abused and exploited by illegal aliens for decades,” an unnamed DHS spokesperson said in a statement. “President Trump and Secretary Noem are returning TPS to its original status: temporary.”

Trump has also moved to end the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program, a separate process that helps people forced to flee their homelands resettle in the United States after being thoroughly vetted. Twenty-four hours after a federal judge blocked that effort on Tuesday, the State Department canceled contracts with refugee resettlement organizations across the country, effectively terminating the program.

At the same time, Trump has offered refugee status to white South Africans, whom he claims are victims of discrimination because of a government policy designed to return land that was seized from Black South Africans during the white-minority apartheid regime that ruled the country until the 1990s.

Rep. Michael Baumgartner, a Spokane Republican who sits on the House Judiciary Committee, which has jurisdiction over immigration, said he sympathizes with TPS holders but believes the program shouldn’t last forever. Congress should pass immigration reform, he said, so that presidents don’t decide U.S. immigration policy by fiat.

“If I had the choice to live in the United States or Haiti, I absolutely would choose the United States of America, but that also doesn’t mean the program wasn’t meant to be temporary,” Baumgartner said. “From an individual standpoint, I have a lot of sympathy for folks. But the reality is, as a policymaker, we have to have secure borders and an immigration system that rewards people who enter the country in an orderly and lawful fashion.”

Dalcima arrived in the United States after waiting in Mexico for 11 months for an appointment with U.S. immigration authorities that she booked through CBP One, a phone app created by the Biden administration in an effort to stem a flood of migrants who were crossing the border illegally to claim asylum, overwhelming courts.

The thought of returning to Haiti terrifies Dalcima, whose father was kidnapped by a gang in 2021 when he returned to Haiti after living in the United States. Assuming he was wealthy, the gang members demanded a $50,000 ransom.

“They say, ‘You have to give that money in 15 days,’ and if not, they’re going to kill you,” Dalcima said. “They’re not bluffing.”

Her father’s wife took out a loan to pay the gangs, losing their home to partially repay the bank. They now live in New York. Dalcima is alone in Spokane while her mother, aunt and sisters live in the Dominican Republic, where Haitians face bigotry and the threat of deportation.

Dalcima has returned to her home country around Christmas, when gangs promise a holiday gift of “no trouble, no crime, no nothing,” she said, so emigrants can return home for a moment of peace.

On one such homecoming, she passed out food to grinning and grateful kids around Haiti. She doesn’t see much of a future for the people who remain there, she said, even while they find joy where they can.

“We just know the day we sleep and wake up, this day we count,” Dalcima said. “You don’t know if you’re going to go outside and return back home. So we have to be happy every day.”

In Spokane, she sees a life for herself giving sonograms to pregnant women, overjoyed by just the thought of listening to fetal heartbeats and seeing babies “even before they come into the world,” she said.

“Here, we are just immigrants,” Dalcima said. “We are father, mother, we are hustler, we are student, who can contribute here. The United States needs immigrants. Immigrants need the U.S.”

Imagining what would happen if she is forced to return to Haiti, she laughed anxiously, suppressing tears. “We have to say, ‘OK, we are ready to die.’ ”

Elena Perry and Orion Donovan Smith’s work is funded in part by members of the Spokane community via the Community Journalism and Civic Engagement Fund. This story has been republished under a Creative Commons license.