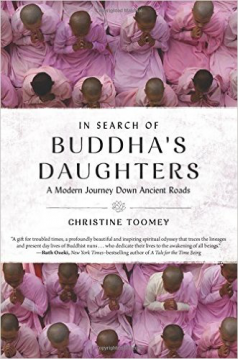

[box type=”info” align=”” class=”” width=””]In Search of Buddha’s Daughters: A Modern Journey Down Ancient Roads By Christine Toomey 370 pp., $24.95 The Experiment Press, 2016[/box]

British journalist Christine Toomey had decided to study the role of nuns in Buddhism when both her parents died within months.

That loss added a personal dimension to her study, leading her to believe that Buddhism could help, “my own search for deeper understanding and a wisdom that would heal.”

Although in her book “In Search of Buddha’s Daughters: A Modern Journey Down Ancient Roads,” Toomey focuses on the role of nuns in various Buddhist traditions, she also offers a useful history of that religion, as well as insight into its teachings.

That view is not universal. The Dalai Lama has said that his successor might be a woman because, “women have a greater capacity for compassion.”

There is no single path that leads women to become nuns. Aspirants leave marriages, well-paying jobs and other commitments to pursue a rigorous schedule in Buddhist nunneries.

Tenzin Palmo, who grew up in London, was 21 when she was ordained as a novice nun in the Himalayas. She spent 12 years alone in a cave, where her days began at 3 a.m. and were divided into three-hour periods of intense meditation. Local villagers brought her food. She believes that women should be eligible for ordination as monks. At a Buddhist temple in San Francisco nuns rise before 4 a.m., eat only one meal a day and sleep sitting in an upright meditation posture.

Not all nuns are drawn to lives of little sleep and lengthy meditation. Some dedicate themselves to community service. Robina Courtin, whom Toomey calls, “a bundle of ferocious energy,” ordained as a nun and founded the Liberation Prison Project to offer spiritual teachings to thousands of inmates, principally in the United States and Australia.

Toomey’s odyssey took her to Nepal, Burma, India and Japan, as well as the United States and France. Nuns tell heartbreaking stories of horrific torture inflicted on them by soldiers in Tibet as part of a Chinese campaign to exterminate Buddhism.

Buddhism has flourished in the West in the past half century with a decrease in monasticism and an increase in secular practice. Lay Buddhists strive to follow basic teachings about meditation and mindfulness, feeling no pressure to become monks or nuns.

[disclosure: I host a Buddhist meditation group in Connecticut].

Toomey does not avoid difficult issues, such as the ongoing Buddhist persecution of Muslims in Burma and sexual abuse scandals involving Buddhist teachers. In other words Buddhism is not immune from the violence and abuse that scar other major religions.

The Buddha never claimed to be a god or special religious figure. Instead, he called himself an ordinary person who had discovered a path to end suffering and increase happiness through concepts such as impermanence, non-attachment and non-judging.

Toomey has written an insightful book about a religion that has attracted a growing number of followers in the United States. I wish she had devoted more space to her own spiritual journey. Perhaps that is a subject for another book.