Last post, I indicated that many American Christians are using self-interest as the main determining factor in selecting their church affiliation. A transaction based on a “serve-me” attitude. And really, why would we expect any different? We shop for everything else, why not our church as well?

The 21st century worldview that places the individual as one of its highest values and emphasizes the moral right of individual choice has given rise to the phenomenon of “church shopping.” America was founded on the notion of religious autonomy and that a centralized state religion would not be allowed to exist, thus setting a context in which several experiential options are possible. Increased mobility allowed the opportunity of visiting multiple congregations any given Sunday. People have therefore been able to choose which church, if any, they will attend.

Paul Metzger asserted that consumerism holds as its highest good, “giving consumers what they want, when they want and at the least cost to consumers.” According to this consumerist ethic, churches perpetuate themselves by satisfying the needs of their ‘customers,’ thereby making personal experience authoritative. Just like the armchair quarterback who never made it past eighth grade football judges a professional coach as a “fool” for calling a particular play, many congregants put a potential church, its staff and its members, through a ringer to determine if they are worthy to meet personal criteria. And yet, as Rich Stearns was quick to point out, “If we fail to give, serve, pray, and sacrifice, we cannot expect our pastors to compensate for our own lack of commitment.”

Darrell Guder claimed, “North American religiosity is becoming more pluralistic, more individualistic, and more private.” The church is often seen as a vendor of various religious services and agendas. People often choose a church based on the services or programs if offers and competition is intense.

Effects of this mentality are numerous. Christians are implicitly taught how to pursue Christianity based on their personal preferences, which works to reinforce race and class divisions based on personal preference. Additionally, according to Donald Bloesch, it fosters a moralist mindset concerned with external acts that help assimilate one to church culture rather than dealing with matters of internal transformation. The result is many church congregations that hoard their resources rather than take on the biblical discipline of stewardship. For example, in 2002, the George Barna Research Group asked pastors to rate the highest priorities for their churches. Answering from a list of categories, 79 percent listed worship; 57 percent, evangelism; 55 percent, children’s ministry; and 47 percent, discipleship programs. Only 18 percent said that “helping the poor and disadvantaged people overseas” was of “highest priority.”

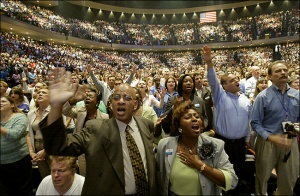

Kevin Dougherty asserted that following a consumerist ethic also fosters a lack of diversity because disciples are raised in a context that is based on their personal preference. This produces a club mentality based on affinity groups where “neither congregations nor parishes are remotely close to approximating the diversity of wider society.” This issue comes directly out of a consumerist-preference driven mentality that avoids the difficulty of interacting with other cultures and classes.

Currently, many people define their communities through leisure, work and friendships, not their locale. Because of the pervasiveness of the consumer culture it is most convenient for churchgoers to attend a church that caters to their kind of people. This is not only true for leisure-based affinity, but also of race and class. With the increase of alternate activities offered on Sunday mornings, churches have provided alternate times. The result is what Neil Burgess labeled: “a congregation of soccer moms and football dads, café churches, or cell churches, to name a few.” This further petrifies the networks in which such people exist, often to the detriment of any possibility for cross-contextual experience.

By marketing to a niche target group and focusing on meeting their specific needs, many churches create communities that have no appreciation of, or interaction with those outside of their affinity groups. Even though these churches can grow to incredible size, most congregants still operate within the same social status or class. For example, to address such a problem, megachurch Willow Creek sought to produce deeper relationship by shuffling people off into small groups. According to Metzger however, no matter how small you break up a homogenous group, it will still be vanilla, “Homogeneous, small-group breeding grounds nurture small-minded and shortsighted attempts to address race and class divisions.” By stressing numbers and consumer choice, many churches have in fact excluded the impoverished, which are incapable of participating in a consumer driven society.

How do you break out of your affinity group? How do you put yourself or your family in a place to interact with those whose lives are not similar to your own?

Fascinating post. Many churches today believe their small groups create the church life they want, but I was always suspicious it wasn’t working very well. I appreciated your insights into one reason why they might not be working too well.

Very Interesting..thanks.

Bruce and Sicco, thanks for taking the time to comment. It is pretty fascinating to me as well. I’m obviously researching only one facet of this whole thing. I hope that others can point me to success stories as well. I have to admit that breaking out of my own affinity group is one of the more challenging things in my life.