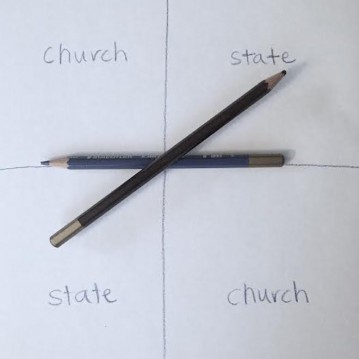

“Charlie Charlie, can we play?” It’s a simple game — you place two pencils crossed on a piece of paper, one balanced on the other. The paper has “yes” and “no” written in the four sections made by the pencils. You ask questions of the supposed spirit, “Charlie”, and the top pencil pivots to point to the yes or no answers.

Basically, its a simplified ouija board you can make out of the two most readily available supplies in any school classroom. It comes as no surprise that the #CharlieCharlieChallenge became a viral sensation that undoubtedly has caused a lot of headaches for teachers.

Schools have begun banning Charlie Charlie — again, no surprise — but the reasoning behind the bans is what has me shaking my head.

This story came to me from an 8th grader at McLoughlin Middle School in Pasco, Washington (edited slightly for clarity and to keep everyone anonymous):

“We were in the corner of the classroom playing the game, and the teacher thought this kid was showing pictures from a trip, so she told him to bring it up to the projector screen. He was like “all right” and he set it up and made the pencils balance. “The whole class started chanting ‘Charlie, Charlie’ all in sync. The teacher turned around and ran across the room and snatched our pencils up, and said ‘we’re not contacting anybody, we’re not doing any of the ouijai shit in this classroom’, and then wrinkled up the paper and broke the pencils in half. “I asked her, ‘Why? It doesn’t even matter.’ “‘Because I’m Christian and we’re not doing any of this stuff in this classroom. You can do it in any other classroom, but not this one.’”

According to the student, the phrase “ouija shit” is an exact quote. She reportedly cracked up so much the teacher sent her out of the classroom.

I even came across one video on Twitter which shows a teacher in a public high school crumpling up the game “In the name of Jesus.” I’d like to give that teacher the benefit of the doubt and assume he just has a great sense of humor, but it really is hard to say, especially when a bona-fide Catholic exorcist warned that those playing Charlie Charlie “can suffer much worse consequences from the demons.”

The mother of a 5th grader at McGee Elementary in Pasco told me the game had been banned there due to children playing it at recess, and a school counselor was going from classroom to classroom to warn the kids not to play the game. She contacted the school to see what their rationale was, and gave me this transcript from her conversation with the school counselor:

“Some kids have tried to play it at recess and we have made it so that it’s not allowed to be played here whatsoever as it’s not appropriate and some kids have been impacted. It makes them worry and get scared. It has scared quite a few of our kids. The schools position is it’s not to be played and to be reported if any kid sees it being played. Fun privileges this week are up for being lost if people choose to play the game.”

When asked why kids would be punished for playing a make-believe game, she said “Some families take these things very seriously.” When the parent continued to question how one student could be punished on the basis of another parent’s religious beliefs, the counselor said “It’s what’s best for the social and emotional health of the children.” The school has taken the potentially illegal position of limiting children’s activities based on a particular religious viewpoint.

A parent in Chicago was upset when her daughter was traumatized by the game. “She was screaming, she was crying,” Shanetris Moore said. “She was shaking.” Moore went on to describe the game as “witchcraft” and believed the school had failed its responsibility to police students and keep them from playing it. Moore seems oblivious to the fact that “witchcraft” is a real — and constitutionally protected — religious practice, which I’m sure has absolutely nothing to do with the origins of Charlie Charlie. How would she react to a student practicing their sincere Wiccan beliefs during recess?

If your child is scared by a pencil reacting to air currents and the force of gravity, that’s on you. It probably doesn’t help ease the trauma when you reinforce that the child was actually contacting a demon. Both of the Pasco students from the stories I told above — an 8th-grader and 5th-grader — were raised without religion, and couldn’t understand why Charlie Charlie was such a big deal. They were never taught to jump at shadows or see the face of incarnate evil in any strange occurrence.

Teachers and administrators are understandably in a tough place here. If the game is being played during class time and distracting from education, of course it is a teacher’s prerogative to shut it down. What a teacher or any school employee should never do is support or assert a religious viewpoint, and implying that Charlie Charlie is anything but a parlor trick is doing exactly that. If schools want to ban students from contacting spirits on campus, does that include the ever-popular morning prayer ritual by the flagpole? Does it include a student making a quick sign of the cross before an exam (perhaps in a similar attempt to receive answers from beyond)? Of course it wouldn’t, because those are constitutionally protected exercises of religion. These overzealous teachers and administrators are essentially defining Charlie Charlie as a religious ritual and then specifically using that categorization to ban it. Either it’s a harmless game, or it’s a religious ritual and the school can’t restrict it when it’s not interfering with class time.

What is a teacher to do when children are genuinely frightened by a silly game? Use it as a teaching opportunity. Without weighing in on whether demons exist or not, you can easily show — without risk of possession — that a pencil balanced on a fulcrum will move entirely on its own without any written words or chanting. They’ll see that it’s nothing to be scared of. I’m sure most students have played the old classic, “Bloody Mary”, as well — that could be another opportunity. Have them stare into a mirror in a dark box and notice that random shapes start to coalesce without any otherworldly intervention. Explore the possible explanations. Hint: it’s most likely the Troxler effect. Use the curiosity they are showing about the Charlie Charlie game to encourage investigation and understanding instead of fear and prohibition.

Most children, given the opportunity to use critical thinking, are able to offer thoughtful, rational explanations for ‘supernatural’ phenomena on their own. Of course, that would require the teachers to not run screaming from the room in the first place.

This is really great. Thanks for it.

I think The First Evil summed it up best: “It’s not about right. It’s not about wrong. It’s about power.” In many communities, the power of religion to mobilise parents around an issue is immense. Moreover, educators are already living and working under a misroscope. So I think it’s understandable that they’re more afraid of being swarmed by fundie parents than they are about the far more remote possibility that the ACLU will bring a court case over a stupid game. Granted, giving in to that fear is morally wrong, but given their relative powerlessness, I don’t think it’s reasonable to expect otherwise from them. I hope I’m wrong.

Great article Steven!

Very thoughtful viewpoint. Thanks for sharing!

Ihave no problem with a little bit of magical thinking to enliven a dull day at school. Most children know the difference, especially when the parents are smart enough not to be terrified by makebelieve.

This is really true because they can easily solve some problem if they think critically. Thus, they have the power to implement something especially if they wanted to solve some problem.