The new movie about Steve Jobs is short on anything explicitly religious. Like its main character, however, it’s got a thread of transcendence running through it.

The truth about Jobs and religion may be that, in this arena as in others, he was ahead of the cutting edge.

The film isn’t making the purists happy, in part because it takes too many liberties with history. But it’s not a documentary. I’ll go against many of the reviews and say that Ashton Kutcher does a pretty good job at representing the personality found in Jobs’ speeches and in what has been written about Jobs — particularly in the massive authorized biography by Walter Isaacson.

One quote in that book, from one of Jobs’ old girlfriends, pretty much captures the character in the film: “He was an enlightened being who was cruel,” she told Isaacson. “That’s a strange combination.”

The movie gives some sense of a man who could be impossibly inspirational — able to get more from people than they’d imagined. And also an irrational boor.

Apple insiders famously had a phrase to describe the effect that Jobs could have on people: the “reality distortion field.” Which sounds like the power wielded by a biblical prophet, no?

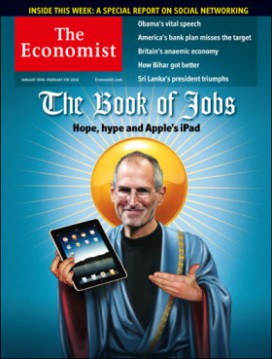

And his creations were described (and derided) in religious terms: the Jesus Phone, the Jesus Tablet. The Economist once ran a cover with an image of Jobs with a halo. New York magazine ran a cover of Jobs with the headline “iGod.”

Jokes have been made — some more pointed than funny — about the resemblance of Jobs and Apple customers to a religious “cult.” (For the record, Apple is not a religion. No faith was ever needed to understand the superiority of the Mac.) And Jobs’ feet of clay extended well past his knees — more akin to the Bible’s Abraham or David than Jesus or any New Testament apostle.

While some people have criticized the new movie as hagiography, Jobs’ flaws get plenty of airing. His womanizing, his denial of his own daughter, his willingness to mix it up in the corporate snake pit — all on screen.

So what did Jobs have to do with religion trends? He was an exemplar, an icon of one of the hottest.

For all the debate about what is really the “fastest-growing religion” in America, the data is pretty conclusive: If “None of the Above” had a headquarters, its membership would only be exceeded by the Catholic Church. (Of course, to paraphrase the old Groucho Marx line, these folks would never join a faith that would have them as members.)

About one in five Americans answer survey questions on whether they belong to a religious group by saying “none of the above,” which has earned them the nickname “nones.”

But most of them say they believe in something that doesn’t fit in any of the standard dogmas. God, prayer, heaven, angels — most of the nones check off one or more of those boxes. That’s where Jobs lived, too.

Early in the movie a young Jobs, while on LSD, hears Bach emerging from a wheat field. He stands and conducts, clearly transported into some deeper connection beyond the visible plants and earth. That happened. Also in the movie, there are hints at Job’s seeking after Eastern religious beliefs. And his frankly nutso diets that he figured helped purify him.

Though the movie doesn’t say so, this spiritual searching followed a childhood of more conventional religion. His parents attended a Lutheran church. And so did Steve, according to his biography, until he bumped up against theodicy when he was 13.

Theodicy is the attempt to explain how an all-powerful, all-knowing, and all-good deity could allow so much human suffering. For Jobs, the question was about children starving in Biafra.

The pastor’s answer didn’t satisfy Jobs. So he never went back. Various accounts of his life describe his eventual link to Zen Buddhism. Apparently he took from Zen an appreciation of simplicity and minimalist design, if not the removal of attachment that Buddhist enlightenment is supposed to bring.

Instead, Jobs was a “none” before anybody knew what that meant. As he told Isaacson not long before his death: “I’m about fifty-fifty on believing in God. For most of my life, I’ve felt that there must be more to our existence than meets the eye.”

But he turned to his own intuitions, not the dictates of any particular religion. That belief in intuition manifested itself in what he did with Apple. Lots of other people were better than Jobs at hardware and coding. Job’s magic was in setting a vision, a philosophy, and then driving the material experts into creating stuff that matched his vision.

But people who devise their own dogmas can fall victim to the same kinds of ills found in established faiths. In Jobs’ case, he may have believed his own hype about distorting reality. When he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, his doctors wanted to operate immediately. They figured they had a good chance at saving him.

Jobs, however, went with his intuition, into fad diets and “holistic” woo-woo that did him no good. By the time he agreed to the operation, the cancer had metastasized and it eventually spread beyond where medicine could help. Doctors differ about whether the delay made a difference.

A few weeks after his death in 2011, a New Yorker cover showed Jobs standing at the heavenly gates, with St. Peter checking him in using an iPad.

A few weeks later, author Eric Weiner wrote an essay for The New York Times. He and other “nones,” he wrote, were hunting for a new way to connect with religious ideas and values:

“We need a Steve Jobs of religion. Someone (or ones) who can invent not a new religion but, rather, a new way of being religious. Like Mr. Jobs’s creations, this new way would be straightforward and unencumbered and absolutely intuitive.”

That was surely one of the many projects Jobs had actually pursued through most of his life. Had he lived longer, who knows? The Steve Jobs of religion may have been Steve Jobs.