Some of my non-Jewish friends aren’t always sure how to approach Judaism. For example, one friend wondered aloud whether it was okay for him to “like” my congregation’s Facebook page even though he isn’t Jewish. The most common worry I encounter concerns the connotation of the word “Jew.” Non-Jews know they can refer to me as “a Jewish person,” but is it politically correct for them to call me “a Jew”? And if not, why not?

Following my usual, highly professional research method, I posted the question of whether “Jew” as a noun is offensive on Facebook. Within 15 minutes, a sizable comment thread had developed. My mother, a longtime Holocaust studies professor, said she encounters this question a lot when she teaches. Her students are usually all non-Jews, and she tells them that calling a Jewish person a Jew is no more offensive than calling someone who practices Christianity a Christian. She thinks the idea that “Jew” is offensive as a noun stems from the mistaken notion that Judaism is a race. A religion and culture, yes. A race? No.

Most of my friends agreed that the intention behind the use of “Jew” is what matters most. (They also shared the opinion that “jew” as a verb is always pejorative.) A friend who is especially knowledgeable about Judaism made the key distinction between “Jew” as a noun and the same word as an adjective. The latter is plainly offensive.

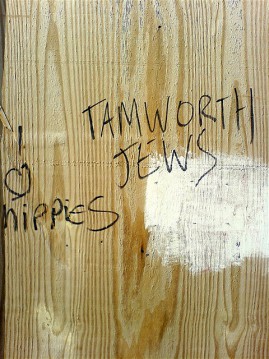

He gave “The Jew producers in Hollywood…” as an example of how an obviously anti-Semitic statement might begin. The same friend indicated that phrases like “the Jew socialists” and “the Jew bankers,” when entered into Google, bring up links to blatantly anti-Semitic Web sites. My mother pointed out that the use of “Jew” as an adjective “reflects a history of anti-Semitism that goes back centuries.”

“The Jews in Hollywood” struck my friend as problematic more conceptually than linguistically, because it reinforces a stereotype and reduces three-dimensional people to their Jewishness. For him, “the Jewish people in Hollywood” is neutral, since it gets into actual demographics: How many people in Hollywood are Jewish?

A friend I lived with at the Ravenna Kibbutz, a Jewish intentional community in Seattle, said that she certainly doesn’t find “Jew” as a noun offensive when it’s used between Jews. I replied that I rarely hear Jewish people discuss amongst themselves whether they prefer to be called “Jewish people” or “Jews.” The question seems to arise only when non-Jews are involved, and they are nearly always the ones asking it.

Since consulting only Facebook seemed less than journalistic, I also turned to Wikipedia on the subject of “Jew.” Its entry on the word is brief but illuminating. Apparently, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, “Jew” was still on the tongues of enough anti-Semites that “Hebrew” became the preferred term. This is how we ended up with the Young Men’s Hebrew Association (YMHA) — which, incidentally, has long since been swallowed by the nationwide network of Jewish Community Centers, and about which the Village People never deigned to write a song.

Interestingly, Wikipedia notes that some contemporary Americans employ the word “Jew” precisely to dispel the notion that its use is always offensive. From this point of view, the phrase “Jewish person” is a “circumlocution” that treads too carefully around a word that is no longer taboo, if it ever really was.

A side note: In the past, anti-Semites often used the Yiddish term for a Jew, Yid. It has since been reclaimed and now signifies roughly the same as mensch: a good person. Wikipedia’s example of Yid’s new, positive meaning focuses on tzedakah (charity): “He’s such a Yid, giving up his time like that.”

A Jewish friend who lives in Edinburgh, Scotland, provided an interesting grammatical insight. She said that she is more likely to refer to a Jewish person as a Jew if the word “is modified by another descriptor, such as ‘British Jews,’” which sounds less awkward to her ears (and mine) than “British Jewish people.” We Jews are closely associated, both historically and currently, with the power of language. It seems apt for us to decide what we want to be called based not only on political realities but also on how the words sound, and how they look on the page.

I’m of Jewish descent and I certainly don’t mind being called that. In these days, someone talking about “Hollywood Jews” and so on more shows their own stupidity than really causes meaningful harm.

Oh, I think it’s possible to show one’s own stupidity AND cause meaningful harm. 🙂 Especially in an area where there aren’t a ton of Jews, one person’s stereotype-laden rant can influence the ignorant in a hateful direction. Not that I’m paranoid and think that happens all the time. I just think it’s important not to dismiss hateful speech, even when it’s “lite,” as harmless. The LGBT rights movement, for example, still has to contend with plenty of bigoted expression that seeks plausible deniability about whether it’s hateful or not.

I know what you mean. Spend any time on an Xbox Live game and you’ll hear plenty of slurs against both groups. I have my multiplayer games set to permanent mute to avoid hearing it all.