NEWPORT, Wash. — There aren't a lot of Buddhists in America — around 3 million or so, according to the Pluralism Project. And if the denomination is a minority then it makes sense that there isn't exactly an abundance of monasteries here either, let alone Buddhist clergy.

Because there's no central administrative office for Buddhists to report to, the demographics of the faith remain unclear. Here's what we do know. Just outside of Newport, Wash., a town of about 2,1000 people, is Sravasti Abbey. It's one of the only monastic communities in the west for Americans to study the Buddha's teachings. What's even more unique is that as of December, the abbey now has five U.S.-born, fully ordained nuns, called bhikshunis. With five ordained nuns at the abbey, official sanghakarmas [Sangha ceremonies] can be held there, including the twice-monthly Posadha [ceremony of confession and restoration of precepts].These particular ceremonies are private. To have the special rites, the abbey only needed four bhikshunis. By this summer, the abbey expects to have six.

“When we first set up the abbey there were three residents, myself and two cats. Now we have two cats and 12 human residents, five of them bhikshunis,” said Abbess Ven. Thubten Chodron. “I think this is a big thing because this isn't a Buddhist country.”

Chodron founded the abbey in 2003, fulfilling her lifelong dream of creating a Tibetan Buddhist community in the states. For a decade she served as resident teacher at Dharma Friendship Foundation in Seattle, but she had no monastic community to call her own. Originally from Los Angeles, Chodron became a bhikshuni in 1986. Like most Buddhist women, she had to travel to Taiwan to receive her ordination.

For full ordination a quorum of 10 fully ordained monks and 10 fully ordained nuns must be present and the ordaining sangha must have at least 10 years experience as fully ordained monastics, according to Chinese tradition. There aren't enough fully ordained monastics in the U.S. or Indonesia, but there are enough in Taiwan and Vietnam, Chodron explained. That was the case 26 years ago and it's still the case today. Full ordination was never established in Tibet because of the difficulty of traveling over mountain ranges from India. “

Our goal is, hopefully, that sometime in the future we'll have enough monks and nuns at the abbey to give the ordination ourselves,” she said.

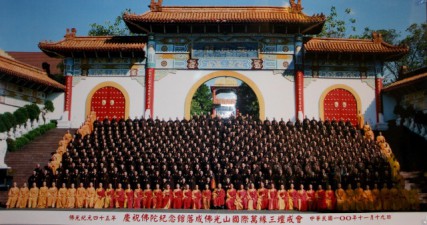

Ven. Thubten Jigme, 60, and Ven. Thubten Chonyi, 58, traveled together to Taiwan at the end of October to partake in the Triple Platform Ceremony, or full ordination where they received the sramanerika, bhikshuni, and bodhisattva vows. Both women gave up their careers and possessions to become first-generation, home-grown monastics. They remain in touch with their families. Jigme dropped out of high school as a teenager, later earned her G.E.D. and eventually earned nursing degrees. She's worked at hospitals, clinics and classrooms, and before moving to the abbey she worked as a psychiatric nurse practitioner in Seattle. Jigme met Chodron at a retreat in 1998 and said she knew immediately that she found her spiritual path.

“It has been a very organic journey,” Jigme said. “I grew up in a family that had little spiritual interest, and I really didn't pursue spiritual practice but put my effort into my career. Over the years, however, I realized I had a spiritual longing and began a search.”

Almost eight years after she met Chodron she decided to attend a retreat at the abbey. There, Jigme said, she experienced the power of Buddha's teachings and began to see a difference in her thoughts and actions.

“I realized I would need the support of likeminded people to develop these qualities,” she said.

She moved to the abbey in 2008 and took her novice vows in 2009. Saying goodbye to her friends, colleagues and patients wasn't easy, but Jigme said the transition was good for her.

“Saying goodbye to them … was another peeling away of worldly involvement. Then, finally, the process of letting go of all the belongings I had accumulated for 56 years was another huge process. But the interesting thing was as I sold and gave away my belongings, I got happier and happier,” she said. “Giving up my worldly identities left me feeling, 'Okay, now who am I and what is my role?' I'm still defining this question as I try to embody the teachings of the Buddha and let go of the strong identity of I.”

Chonyi has been a student of Chodron for more than 15 years. She met her at the Dharma Friendship Foundation. At the time Chonyi was working as the co-owner of Reiki Healing Arts Center. She supported Chodron and became a lay founder of the abbey. For several years she toyed with the idea of becoming a monastic and in 2007, finally committed, Chonyi said.

She and Jigme have been training for full ordination since they arrived at the abbey, but the final lessons took place in Taiwan. Chonyi explained that the intense training included everything from lessons on meditation and Buddhist history to classes on standing, sitting and eating properly. There are 348 precepts a bhikshuni must follow.

“When you have a calm body that's focused and at ease, it has an influence on everybody around you,” she said.

Though exhausting and overwhelming at times, Chonyi said the training strengthened her faith and brought her closer to her fellow residents.

“I got a sense of what my responsibility is for helping to hold the value of the community,” she said. “I feel a very strong responsibility for establishing something that will be here, hopefully, for hundreds of years after us. We're creating a space for the people behind us.”

The novice and fully ordained nuns at the abbey teach classes in Spokane and the surrounding areas and host events and retreats on their property. Because interest in the abbey is growing, the residents are currently fundraising and hope to build a new building that can accommodate more people.

For information visit http://www.sravastiabbey.org/.