Bishop John Shelby Spong has spent most of his life struggling against biblical literalism and modern fundamentalism which sprang from it.

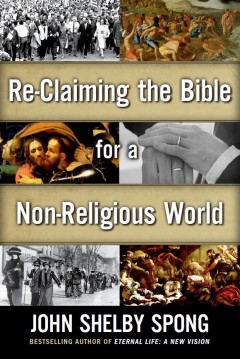

He continues that fight in his most recent work “Re-Claiming the Bible for a Non-Religious World.” In this book he repeats a number of things that are, well, worth repeating.

The Bible isn't history, and it isn't science, two disciplines that had not been developed in the modern sense when scripture was written. It is rather the product of pre-scientific cultures (note the use of the plural) whose basic assumptions were foreign to the positivism that has come to dominate modern thought. Therefore we are bound to misunderstand scripture if we read it through the lens of our worldview. Indeed, only when we seek to understand the cultures out of which it came can we hope to grasp what it is saying to us now.

He also wonders out loud why these basic facts, long taught in mainline seminaries, are not more widely proclaimed in the mainline churches. It's a good question. He is correct as well when he ascribes at least part of the decline of the institutional church to the increasingly common conviction that since we can't take the bible literally it isn't relevant and therefore the only way to restore the importance of scripture is to rediscover how to read it and to appreciate the truth it tells us from a different perspective. Spong's expressed desire is to reacquaint an increasingly secular society with the power and truth of scripture and in this light he summarizes his perspective, and the purpose of this book this way,

“I am not the enemy of the Bible. I am the enemy of the way the Bible has been used….I want to take my readers into this Bible in a new way. I want to plumb its depths, scale its heights and free its insights from the debilitating power of literalism.” A laudable goal, even if stated with some bombast.

Sadly, this book suffers from the same defect as most of his other work — Spong's need to launch attacks on a wide variety of people whose only offense is to find value in the forms of worship and kind of theology he no longer sees as helpful.

Three examples will have to suffice for the multitude that chokes this book nearly to death. Early in the book he describes the procession of the gospel found in many churches of the catholic tradition as “folderol.” In his chapter on Micah he can't resist a gratuitous slap at the common custom of having a time for announcements in church. “Sometimes these announcements are overt,” he tells us, “while at other times they are camouflaged under the guise of prayer.” “Camouflaged?” What is that about? Not content with this insult, he goes on to assure us that, “These public displays serve to remind people that they are not forgotten and to massage delicate egos.” Really? Is there no other reason for announcements than this? He also demonstrates a mastery of the Ad Hominem argument.

In his chapter on “The Prophetic Principle,” Spong reminds us that Martin Luther King Jr. was wiretapped by ,”none less than J. Edgar Hoover, Federal Bureau of Investigation head, who we now know as a deeply closeted and self-denigrating homosexual.” Yes, we do now know that Hoover was gay, but why the psychologizing, and what does that have to do with anything? What he conveys by all this is not a clear, convincing and courageous argument, but a smug self-righteousness that by the end of the book becomes intolerable. The bulk of “Re-Claiming the Bible“ is a survey of the biblical books. It is dotted with poor and outdated scholarship.

He is certain Daniel belongs in the Apocrypha, which demonstrates a misunderstanding of how the Apocrypha came to be, and also ignores the value ascribed to this book by Judaism, which placed it in the wisdom literature of the Hebrew Bible, where it belongs, rather than among the prophetic books, where it doesn't. He is also surprisingly conservative — remarkable in itself — and shows no knowledge of the work of Thomas Thompson and the Copenhagen school, nor of John Van Seter, both of whom as early as the 1970s destroyed the thesis that the patriarchal narratives have any history in them at all. The effect is embarrassing; he presents as settled facts theories that were largely debunked more than 30 years ago in the very scholarly circles he wants more widely advertised. When he comes to the New Testament he can't resist repeating his oft stated conviction that the theology of St. Paul is best understood only after we realize that he was — evidently like J. Edgar Hoover — a “self-denigrating homosexual.”

Again, it isn't enough to know that Paul was gay; it is the psychology of Paul that is crucial, for according to Spong the apostle hated himself. This tendentious thesis depends upon a truly remarkable discussion of Paul's use of the term member, and an often repeated and certainly mistaken understanding of the seventh chapter of Romans. The result is a complete misunderstanding of Paul's theology. Paul's argument is not that he tried to be good and couldn't. Paul's argument is that he tried to be good and succeeded, but it didn't get him what he wanted, life with God. Paul's theology does not dwell on how we feel about ourselves subjectively, whether we harbor good or bad feelings about ourselves.

Paul is concerned about how we actually stand before God, regardless of our personal feelings about ourselves. Spong and many others seem not to understand that Paul is arguing that the cross wakes us up to our true position before God and thus destroys our subjective sense of righteousness and supplants it with the true righteousness that is ours as a gift of grace. As a matter of fact Paul's own personal testimony is that he felt plenty good about himself, all the time, and that he discovered in light of the cross that this personal sense of righteousness was driving him away from, rather than toward, the God he so longed to serve. It is fine to feel good about yourself, by the way, just don't imagine your subjective feelings describe your true position. I disagree with the critics of Spong who declare that the “Paul was gay” thesis is preposterous. It isn't preposterous, though I too don't believe it. It is rather that it cannot be proven, depends upon a misreading of a crucial text, has nothing to do with Paul's gospel and therefore distorts altogether what Paul is saying. Yet Spong hangs on to this notion for dear life, much to the detriment of this book.

In the end the book is not unrelievedly terrible, but unless you are ideologically wedded to his perspective, or hate him enough to search his books for more ammunition against him, this one isn't worth reading.

Nice review- I appreciate the insights.

Thank you for a good, thoughtful review!

Me too!

You are right, and love you take down of his view of Paul. As a gourmet of irony, I do find Spong’s theory of Paul sexuality comes out of Spong’s cultural context, similar to what he criticizes the Literalists for doing, is very tasty, indeed.