Guns and Gun Control

June 5, 1968. Midnight. Early Wednesday morning just two days before my high school graduation.

I had just turned off the TV after watching results of presidential primaries in California and South Dakota.

I had been a campaign volunteer for Robert Kennedy in the Oregon presidential primary a week before and was on stage with him during an appearance at the Lane County Fairgrounds the night before that vote. Kennedy had lost to Gene McCarthy in Oregon. It was close, but McCarthy was viewed as more anti-war than Kennedy in a state where the Vietnam War had become the overriding issue and where outsider mavericks were venerated.

So, it was gratifying to see Kennedy take California, immediately moving to the head of the primary pack. After California, he would be the favorite for the Democratic nomination in that pivotal 1968 election to replace Lyndon Johnson.

Then my phone rang.

It was my girlfriend, and she was agitated. “Turn on the TV,” she shouted. “Bobby has been shot.”

Nothing else needed to be said. It was 1968. Martin Luther King Jr. had been killed the previous April. America’s cities were roiled by demonstrations against racism and the Vietnam War. Some had turned violent.

In that turbulent year, it had seemed inevitable that violence would strike the presidential campaign. But Bobby? Shot just after midnight on June 5, he died 26 hours later.

The shooter was a 24-year-old hotel busboy, Sirhan Sirhan. His weapon, an Iver Johnson Cadet 55-A revolver, a so-called Saturday night special, widely advertised, cheap and easily purchased.

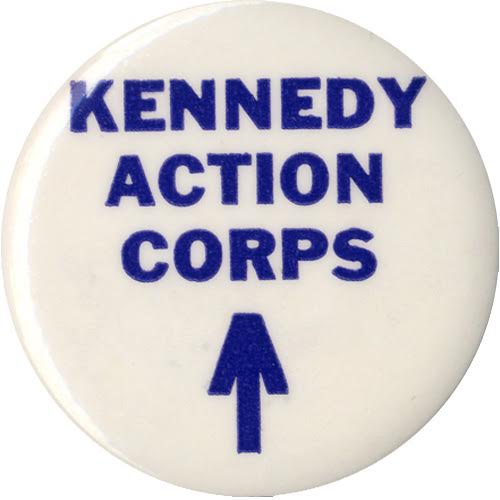

Kennedy had developed a strong ground force during the campaign. His young volunteers were dubbed the “Kennedy Action Corps.” In the hours after his killing, no one was sure what would happen. But there was agreement his powerful ground force should carry on in some way.

That was why, little more than a week later, I found myself canvassing neighborhoods near the University of Oregon, carrying petitions calling for strong gun-control legislation specifically aimed at limiting access to those Saturday night specials.

And…nothing.

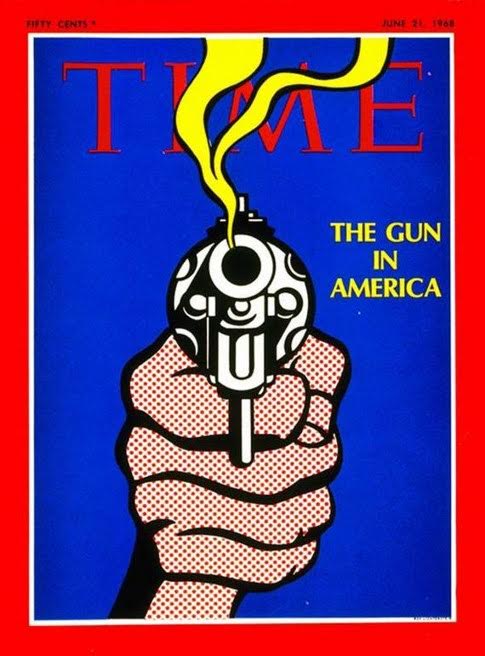

The June 21, 1968 issue of Time magazine, just weeks after RFK’s murder, featured a striking cover and an inside report summarizing the debate over gun control. Re-reading that story now, it is clear the basic outlines of the debate have been unchanged for more than 50 years.

What has changed is the nature of gun ownership. That long-ago dispute over Saturday night specials seems quaint. Arguments over the rights of hunters and recreational shooters have morphed into debates over the ability of just about anyone to obtain military-grade weapons. And there is a new, technology-driven complication – so-called ghost guns that can be “printed” by in-home 3D printers and which do not carry serial numbers and so allow users to avoid federal background checks.

Another major shift since 1968 – the frequency of mass shootings and the carnage wrought by those military-style weapons. In every recent mass shooting, the killer’s weapon of choice was either an AR-15 or AK-47 assault weapon, or a high-powered, large magazine handgun.

There were four mass shootings in March, a total of 27 dead. The usual thoughts and prayers followed. Once again, various gun control bills have been suggested or even introduced at state and federal levels. None will pass or survive eventual court challenges or survive the refusal of some local police to enforce the laws that do pass.

Although the national gun-control debate exploded after the MLK and RFK assassinations, it must be said that nothing has come from it. The powerful gun lobby has managed to completely block regulatory efforts, even succeeding in repeal of the assault weapons ban in place for only 10 years.

It serves no meaningful purpose to try to argue in this space the merits of some limited gun-control measures. The battle lines have been drawn for more than 50 years and sides are more entrenched than ever. Why waste time on debate?

Are we sentenced then to indefinitely experience gun-caused bloodshed? Simple answer: Yes.

There may come a time when outrage over the latest mass shooting fuels some meaningful regulatory response. But we have multiple, horrific mass-casualty events in the last several years that produced temporary sound and fury and those thoughts and prayers.

I remember walking home from my Kennedy Action Corps petition effort sad, frustrated, and depressed. Hours going door-to-door had produced only a handful of signatures.

Fifty-two years later, when it comes to gun violence and the possibility of meaningful, effective gun control, my emotions are the same.