Columbus Day or Indigenous Peoples Day? Getting to the heart of the American identity crisis

By Robert P. Jones | Religion News Service

Ahead of the Fourth of July earlier this year, I wrote a column for Religion News Service about two competing plot lines in the stories we Americans tell about ourselves: an egalitarian narrative that draws on the Declaration of Independence’s assertion that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights”; and an older hierarchical tradition of domination consolidated in a 15th-century church doctrine, known as the Doctrine of Discovery, which declared Europeans and Christianity (often conceptualized as inseparable things) to be superior to all other races and religions.

The former has straightforwardly called for the uplifting of all people as equal bearers of the image of God, while the latter has justified the murder and enslavement of Black and Brown people across the globe, while proliferating a duplicitous vocabulary — explorers, crusaders, settlers, founders, pioneers — that still blurs our moral vision and confounds our discussions today.

With the holiday this Monday, we see these incompatible narratives uncomfortably juxtaposed. The official federal holiday schedule lists “Columbus Day” as one of 12 national holidays, but my ical feed from Google for “Holidays in the United States” loads “Indigenous Peoples Day” above that on my calendar.

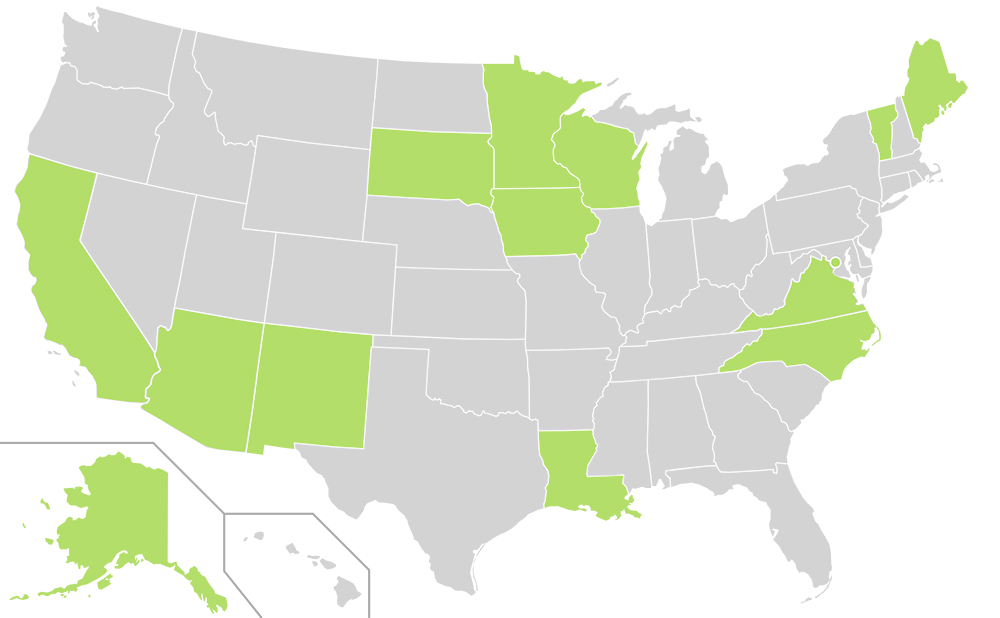

The relatively recent development of Indigenous Peoples Day illustrates how ‘in medias res’ we are with our contested national story. Indigenous Peoples Day was first celebrated in Berkeley, California, in 1992 on the 500th anniversary of the arrival of Columbus in the Americas. Since then, 13 states and a number of cities (including my home city of Takoma Park, Maryland) have formally designated the second Monday in October as Indigenous Peoples Day, or Native American Day.

During the 2020 presidential election, the competing holiday designations became part of the partisan drama. Joe Biden issued a declaration honoring Indigenous Peoples Day and held a virtual celebration featuring two Native American women serving in Congress and tribal leaders and Native musicians. At a campaign rally in Muskegon, Michigan — a city that stands on Odawa, Ojibwe and Potatawomi territory and takes its name from the Odawa language — Trump mocked this recognition while wearing his red “Make America Great Again” hat in front of a raucous crowd of supporters:

Joe Biden attacked Christopher Columbus by refusing to recognize Columbus Day. And he wants to change the name of Columbus Day to Indigenous Peoples Day. Who likes that idea? Who likes it? (crowd boos). What the heck are you saying? … Not as long as I’m president, I can just tell you that (crowd cheers). This is what we’re dealing with. This is what we’re dealing with. The radical left is eradicating our history, and Joe Biden will let them do it.

As I’ve noted in previous writing at The Atlantic, interrogating Trump’s uses of pronouns quickly illuminates the bigotry in his speech. Who exactly does Trump have in mind when he says “our history”? To what period of history does Trump’s nostalgic visions of American greatness refer? In Trump, the spirit of the Doctrine of Discovery has been made flesh and dwells among us.

Here’s a quick summary, from my Fourth of July column at RNS, of how the Doctrine of Discovery has become embedded in U.S. policy and law:

The Doctrine of Discovery was used by Thomas Jefferson as president to justify the Louisiana Purchase and the mistreatment of Native Americans in that territory. It was formally incorporated into U.S. law in Johnson v. M’Intosh in 1823, which held, by unanimous decision, that the expulsion of Native Americans from their lands was justified by “the character and religion of its inhabitants … the superior genius of Europe … (and) ample compensation to the (Native Americans) by bestowing on them civilization and Christianity, in exchange for limited independence.” Our continued reliance on that legal precedent was the key reason that the U.S. was one of only four countries, out of 147, to vote against the adoption of the Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples at the 2007 United Nations General Assembly.

To the contemporary ear, the tenets of the Doctrine of Discovery seem too harsh to be said out loud, at least in mixed company. If one does not deny their plain meaning outright, the temptation is to banish them to the dustbin of history, as archaic notions from a pre-Enlightenment past. But these sentiments are, disturbingly, still animating both our legal traditions and our political divisions.

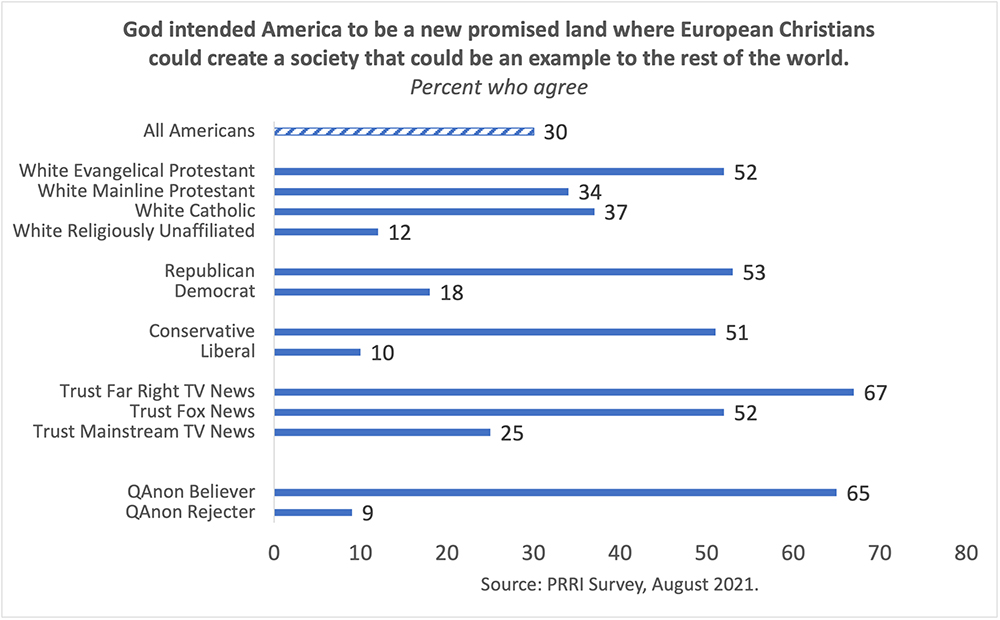

In August, PRRI found that three in 10 Americans agreed with this statement, which captures the heartbeat of the Doctrine of Discovery: “God intended America to be a new promised land where European Christians could create a society that could be an example to the rest of the world.”

Notably, majorities of white evangelical Protestants (52%), Republicans (53%) and political conservatives (51%) agree with this statement. Majorities of Americans who most trust Fox News (52%) or far-right news sources such as OANN and Newsmax (67%) also agree. And there’s evidence that this vision of white Christian American exceptionalism is also driving the QAnon conspiracy movement. Nearly two-thirds (65%) of Americans who affirm the basic tenets of QAnon agree that God intended America to be a promised land for European Christians.

Disturbingly, this belief in America as a divinely ordained white Christian nation — which has blessed so much brutality in our history — remains linked to denials of our past and support for political violence and anti-democratic sentiment in the present. Among those who agree that God intended America to be a promised land for European Christians:

- 62% believe that the impact of America’s history of slavery and racism on life now is exaggerated.

- 55% believe in the “replacement theory” idea that immigrants are invading our country and replacing our cultural and ethnic background.

- 63% believe Trump is a true patriot.

- 39% — nearly two out of every five — believe true American patriots may have to resort to violence in order to save our country because things have gotten so far off track.

In 1964, James Baldwin wrote, with piercing vision, about the crisis of identity Americans perpetuate by holding onto mythologies of American innocence. As Baldwin noted in “Nothing Personal”:

It is the very nature of the myth that those who are its victims, and, at the same time, its perpetrators, should, by virtue of those two facts, be rendered unable to examine the myth or even to suspect, much less recognize, that it is a myth that controls and blasts their lives … To be locked in the past means, in effect, that one has no past, since one can never assess or use it: and if one cannot use the past, one cannot function in the present, and so one can never be free. I take this to be, as I say, the American situation in relief.

Those competing American stories, never resolved, are erupting through the surface today. As we reflect on “our” heritage on Monday, may we do so with a clear-eyed honesty that finally sets us free from the exhausting efforts of maintaining a mythical vision of the past that prevents us from embracing a liberating and egalitarian future.

(Robert P. Jones is the CEO and founder of the Public Religion Research Institute and the author of “White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity.” This article was originally published on Jones’ Substack #WhiteTooLong. Read more at robertpjones.substack.com. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)