‘Sugarcane’ Oscar nomination resonates with Spokane Indigenous directors

News Story by Matthew Kincanon | FāVS News

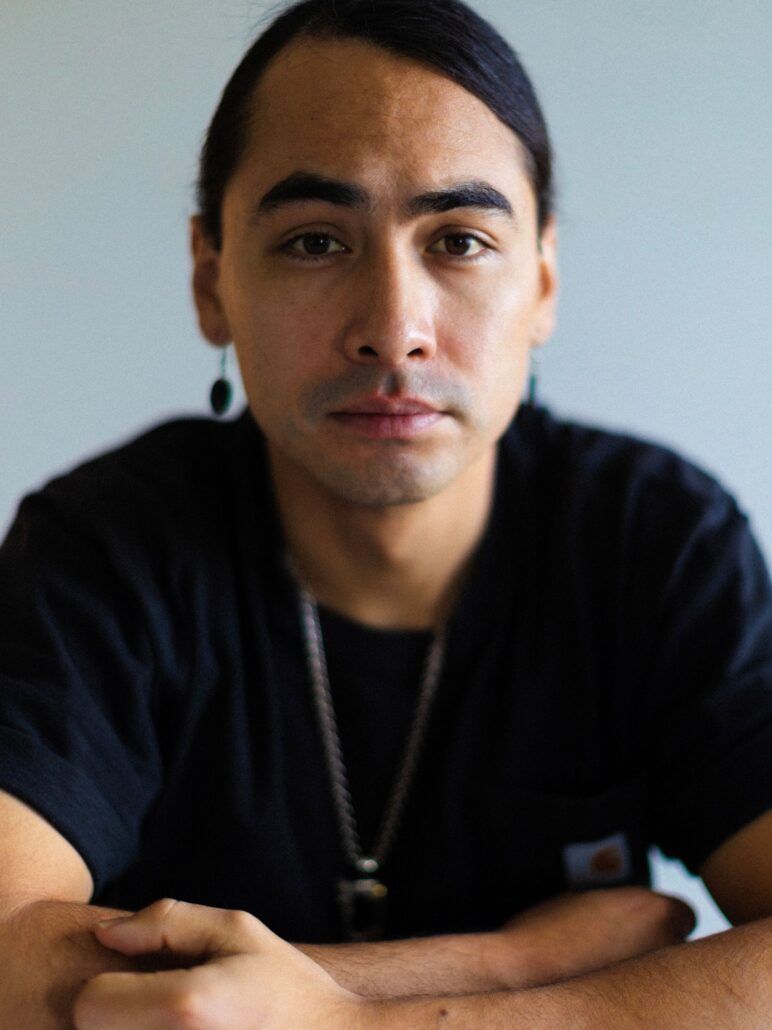

While Indigenous talent has received more recognition recently, no film by a North American Indigenous filmmaker has ever been nominated for an Oscar in the award’s 97-year history. However, that changed this year when Julian Brave NoiseCat (Canim Lake Band Tsq’secen) became the first one for his documentary “Sugarcane.”

The film chronicles the investigation into the abuse and deaths that occurred at St. Joseph’s Mission, an Indian residential school near Williams Lake, British Columbia, shedding light on what happened to Indigenous children at the hands of the Catholic church and government.

“It’s an honor to be nominated alongside my directing partner, Em. We are incredibly proud of the film we made together,” he said. “It is especially meaningful for this overlooked yet foundational chapter of North American history to be seen and grappled with in this way. And I hope the powers that be see the potential in telling untold stories from marginalized perspectives, including and especially Indigenous ones.”

Oscars recognizing indigenous talent

NoiseCat learned of his Academy Award nomination through a flood of text messages after stepping out of the shower. He immediately called his father and other close contacts.

Fellow director and producer Emily Kassie, who was sobbing upon hearing the news, initially couldn’t reach NoiseCat. When she learned why, her thoughts turned to the boarding school survivors and what the nomination would mean for their community.

“Their stories and voices have been buried, ignored and erased for far too long,” Kassie said. “This is their moment and it’s the honor of my career as a filmmaker and of my life in general to help tell this story and to tell it with Julian.”

NoiseCat said they began working on the film when Kassie reached out to him after hundreds of potential unmarked graves of students were discovered at Kamloops Indian Residential School, saying she wanted to collaborate on a documentary.

NoiseCat was initially hesitant to touch this story because, like with many Indigenous families, he said his family has an intimate and painful connection to the residential schools and they didn’t talk about it.

However, two weeks later, when NoiseCat said he would be open to collaborating with her, she told him it was about St. Joseph’s Mission. It was the same school where his family was sent to and where his father was born and abandoned. The two filmmakers spent the last three years in

Williams Lake and surrounding Indigenous communities in the Cariboo region of British Columbia making their film.

While he said his nomination is nowhere as big a cultural moment as when Lily Gladstone was nominated for Best Actress in last year’s “Killers of the Flower Moon,” he hopes “things like this become a trend rather than a historic exception.”

“I better not be the only Oscar-nominated Indigenous director for long,” NoiseCat said.

Spokane filmmaker Misty Shipman (Shoalwater Bay Tribe), who made the short film “The Handsome Man” starring Gladstone and Evan Adams (“Smoke Signals”), was thrilled to see the Oscars recognize Indigenous talent and craftsmanship. She felt the nomination was an acknowledgement of Native people’s skills as filmmakers, storytellers and creatives, and meant more people would watch it.

Treatment of Indigenous people

Regarding the history of the boarding schools, NoiseCat said this is how the land was taken and this is what happened to Indigenous cultures and families. The churches and governments took away kids and often abused them, he said, and histories like this can help people understand the home-grown roots of authoritarianism.

“For the vast majority of Canadian and American history, Indians were not meaningfully free,” NoiseCat said.

For those who watch the film, Kassie said she hopes it does nothing short of correcting the record, help rewrite the hidden origin story of North America and help provoke dialogue and healing in Indigenous communities.

“I also hope that everyone can see themselves in the film, we all can relate to familial pain, trying to understand our parents and make sense of our past and identity,” she said.

NoiseCat said the film has been played to members of the cabinet in Ottawa and Washington, D.C., and they hope it corrects the record of the schools and of a people who have been overlooked and portrayed as vanishing for far too long.

Spokane filmmaker Derrick LaMere (Rocky Boy, Little Shell, Sinixt, Entiat, Wenatchi), who made films including the documentary “Older Than The Crown,” said there are a lot of things the general public needs to learn and unlearn about the treatment of Indigenous people.

“We have to learn about these atrocities to set examples why this can never happen again. Just because the story is difficult, doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be told and shared,” LaMere said.

Impact on Indigenous storytelling

With the nomination’s potential impact on Indigenous storytelling, NoiseCat said he hopes it changes the way their films are made and how their stories are told.

“Our film tries to tell this story in an Indigenous and specifically Secwépemc and Salish way — a way that is true to our ancestors who were deeply rooted in place and tradition, who deeply valued family and community, who spoke of tricksters as forefathers and who acknowledged the power and presence of spirits and the beyond,” he said.

He hopes their film doesn’t just change the phenotype and self-identification of the perspectives in the director’s role, but that it “changes the way we make films, tell stories and see art.”

LaMere said the directors broke through the invisible ceiling and got credit where it was overdue. He described the Oscar nomination as “an affirmation to keep going.”

“To be absolutely honest, it is really easy to quit and move on from this medium, especially when you don’t feel supported or seen,” LaMere said. “But seeing a film with a topic like this breakthrough, it’s reinvigorating.”

LaMere thinks it will lead to more opportunities for Indigenous filmmakers to tell their stories.

“There are so many instances where us as Indigenous storytellers have to filter our story through a non-Indigenous lens,” he said. “Whether it’s because it makes it more digestible to the broader public or merely because we are ‘not experienced enough’ to take a story and apply it to film. We have unimaginable road blocks, and successes like these break through and create a path for the next storyteller.”

Shipman shared similar sentiments; she hopes NoiseCat’s work and the voices of the survivors will inspire more Indigenous people to make films, be brave and tell their stories.

NoiseCat hopes other talented Indigenous individuals get more recognition, including N. Scott Momaday, Louise Erdrich, Connie Walker, Erica Tremblay, Tommy Orange, Tanya Talaga, Sterlin Harjo, Sky Hopinka, Kaniehtiio Horn, Tazbah Chavez, Loren Waters, Jesse Short Bull, Mariah Hernandez-Fitch and all the aunties and uncles out there who tell the best stories and “continue to show us the way.”

LaMere also said he hopes to see Jessie Sears, Indigenous content producer for Oregon Public Broadcasting, get more recognition as she has to wear many hats to uphold OPB’s and her mission to tell truthful and authentic stories.

Shipman is excited for all the work being done through the Native Women in Film Festival and Red Nation International Film Festival, and hopes all Indigenous creators get the opportunity to shine.

The church and atonement

The documentary delves into a dark chapter in the history of Christianity and the Catholic church where Indigenous children were taken from their families and placed into boarding and residential schools.

In recent years, the extent of the abuse and crimes committed at the schools has come to light and the film shares the stories of survivors and what they went through. Other recent films such as Marie Clements’s “Bones of Crows,” have tackled this subject as well with plotlines that detail the abuse Indigenous children experienced at the hands of clergy.

NoiseCat said Christians and Catholics have a lot to understand and atone for; and that there are many Native people who know what the Church did was wrong and yet remain faithful believers.

“If we can live with that contradiction and duality, the least they can do is interrogate the sins of the faiths that we so often still share despite all that has happened,” NoiseCat said.

Kassie hopes the film calls on Christians and Catholics to demand answers from the church and insist they open their records to Indigenous families so they can know the truth.

“I hope it also helps people understand that the practice of faith can exist in concurrence with holding a powerful and corrupt institution to account for their crimes against children,” she said.

Healing and learning

For Indigenous people who are healing from the trauma and intergenerational trauma caused by the boarding schools and genocide, NoiseCat said community, culture, family, prayer, ceremony, love and ancestors will help in the healing process.

“Families that survived this genocide are often silent about their own background, their own truth, their own experience, because that was how we coped with it,” NoiseCat said. “That was how we moved on: by burying what had happened deep within and never letting it out. We would only hear about this history from the perspective of the perpetrators.”

Kassie said the present consequences of the boarding schools still haunt Indigenous communities today, describing how they face the highest rates of suicide, addiction and cycles of violence as a result of six generations of family separation and abuse. She added St. Joseph’s Mission’s death toll is long and remains open.

“‘Sugarcane’ is a tragic story that unfortunately so many Indigenous communities share,” LaMere said. “Be prepared to learn and unlearn a lot of things you thought you knew about the treatment of Indigenous people of North America.”

He added it is an issue that can’t be divided into just an Indigenous issue, but that it is American and Canadian history.

“If we don’t acknowledge and learn from this, we are destined to repeat it. Not to mention it is a beautifully made film. Story and visually,” LaMere said.

Shipman said everyone on Earth should watch the documentary. Every politician, member of the House and Congress, schoolteacher, religious leader and community member.

“The story is brutal, painstaking and important. It is told with respect and dignity for all survivors,” Shipman said. “The world needs to know what happened to our communities, and the residual, lasting trauma that occurred as a result. The film also offers hope to survivors and their children and grandchildren, as it highlights healing through culture.”

The 97th Academy Awards ceremony will be held on March 2. The film can be streamed on Disney+ and Hulu.

Okay, I’m piqued!