By Kimberly Burnham

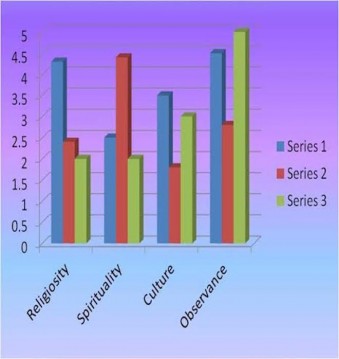

First of all researchers are differentiating between religion, religious observance and spirituality, including spiritual well-being, spiritual coping, and spiritual needs. They are also looking at the intersection of culture and religiosity and whether measuring tools developed in one country for one culture or religion can be used in another country or with another culture. Are the measuring tools reliable, is another consideration.

“Higher levels of religious involvement are modestly associated with better health, after taking account of other influences, such as age, sex and social support. However, little account is taken of spiritual beliefs that are not tied to personal or public religious practice. Our objective was to develop a standardized measure of spirituality for use in clinical research,” said researchers in a 2006 study in Psychological Medicine .

They characterized the core components of spirituality using “narrative data from a purposive sample of people, some of whom were near the end of their lives.” This in itself brings a controversial aspect to the research since there may be a change in a person’s spiritual habits in the face of death or serious illness.

Still their research produced a 20-item questionnaire which “performed with high test-retest and internal reliability and measures spirituality across a broad religious and non-religious perspective. A measure of spiritual belief that is not limited to religious thought, may contribute to research in psychiatry and medicine,” said King, et al.

In a 2011 Malaysian study of people with diabetes researchers measured and defined religiosity and concluded, “Those with higher religiosity amongst the Moslem population had significantly better glycaemic control. Patients who had church-going religions had better glycaemic control compared with those of other religions,” in ‘Does religious affiliation influence glycaemic control in primary care patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus?’

These researchers used the Beliefs and Values Scale (BV), which contains 20 items each with a Likert scale of five possible responses. The range of scores is 0 to 80, with a higher score indicating stronger religious belief.”

Saying, “A questionnaire that transcends specific beliefs is a prerequisite for quantifying the importance of spirituality among people who adhere to a religion or none at all,” researchers in another study favored the Spiritual Well-Being Questionnaire (SWBQ) from Gomez and Fisher (2003).

Health researchers have also sought to distinguish between spirituality and religion. “A major focus of the study was to distinguish spirituality from religion. The attributes of this definition included that spirituality constitutes a “quality”, a “journey”, a “relationship”, as well as a “capacity,” said Janse van Rensburg, et al in 2014 in the Journal of Religion and Health.

It is interesting to note that there is a whole journal, the Journal of Religion and Health, which “explores the most contemporary modes of religious and spiritual thought with particular emphasis on their relevance to current medical and psychological research. Taking an eclectic approach to the study of human values, health, and emotional welfare, this international interdisciplinary journal publishes original peer-reviewed articles that deal with mental and physical health in relation to religion and spirituality of all kinds.”

Another recent study in the International Review of Psychiatry looked at spirituality in the workplace. They consider the impact of culture on the reliability of measures of spirituality. “Research consistently shows that spirituality is significantly correlated with mental health and well-being. Most of the research on spirituality, particularly in the context of the workplace, is conducted with instruments developed in the USA. However, the inter-cultural measurement of constructs remains a concern, because instruments developed in one culture are not necessarily transferable to another culture. In the current study, the transferability of two spiritual measures developed in the USA, namely the Human Spirituality Scale (HSS) and the Organizational Spirituality Values Scale (OSVS) are considered for a sample from South Africa.”

They conclude by saying, “The study provides evidence that the HSS and the OSVS cannot be transferred indiscriminately to a South African sample. This insight contributes to the quality of future research studies in South Africa, not only on the important aspect of spirituality, but also when applying instruments developed elsewhere in the world.”

Fortunately researchers have no shortage of measurement tools to chose from. These can be classified into measures of general spirituality, spiritual well-being, spiritual coping, and spiritual needs including: The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale, Spirituality Assessment Scale, The Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality, The Spiritual Transcendence Scale, The Spiritual Health Inventory, The Royal Free Interview for Religious and Spiritual Beliefs, The Spirituality Scale, The Expressions of Spirituality Inventory, The Spiritual Transcendence Index, The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being Scale, The Spiritual Well-Being Scale, WHOQOL SRPB (spirituality, religion and personal beliefs), JAREL spiritual well-being scale, The Spirituality Index of Well-Being and the Spiritual Needs Inventory, and The spiritual interests related to illness tool (spIRIT).